Archive for the 'Business' Category

Searching for Paul C. Pratt

Paul C. Pratt is the man behind the Gryphel Project, an ambitious software and documentation effort to preserve and extend classic 68000-based Macintosh computers. He’s the author of the wildly-popular Mini vMac emulator, as well as other great tools like disassemblers and ROM utilities. Paul’s been a pillar of the classic Macintosh community for decades. Although I’ve never met him, I’ve exchanged many emails with Paul over the years, and he’s always been helpful.

Paul has gone missing. Not missing in the sense of a family emergency and police search, but missing for over two years from the classic Macintosh community where he’s been an active member for so long. His Gryphel Project site is still up, but there have been no new posts there since April 2021. He hasn’t appeared anywhere else online either, and he’s not responding to emails, nor to messages sent through community forums where he’s a member. Paul doesn’t have much social media presence, and nobody’s sure of his real-world address or phone number.

Maybe some family emergency or health crisis has demanded Paul’s attention since 2021? Maybe he simply got burned out on classic Macintosh topics, and decided to abandon his online identity and walk away from it all? For the past year, concerned members of the community have attempted to get in touch with Paul through various ways online and real-world to confirm he’s OK, or to ascertain what might have happened to him. They’ve not been successful, which is frustrating and sad.

I sincerely hope that Paul’s sitting in a sunny meadow somewhere, enjoying a lovely day and not giving any thought to crusty old Macintosh computers. But with every passing day that he’s not heard from, we all fear the worst. If he’s died, it’s entirely possible that Paul’s heirs might not think or care to tell anybody outside of his immediate family and friends. From his bio we know that Paul was born in 1969 or 1970, which makes him about 52, and the same age as me. That’s not old, but it’s a cautionary reminder that none of us live forever.

Hearing Paul’s story has motivated me to draft a continuity plan for BMOW, in case of my sudden unexpected disability or death. I’ve made arrangements to ensure the blog and the store would be gracefully wound down, and product designs would be transferred to responsible hands to make sure that nothing important is lost.

Read 6 comments and join the conversationEnd of the Global Semiconductor Shortage?

After three very difficult years, BMOW’s experience with the global semiconductor shortage is finally starting to improve. During most of 2020-2023, even common chips like voltage regulators were hard to get, and a few essential chips that are required for Floppy Emu and Yellowstone were completely unavailable for periods of months or even years. I previously wrote about the business difficulties this created in Global Chip Shortage Hits Home, Semiconductor Shortage and Business Threat, and Yellowstone Future Forecast Update. It’s been rough.

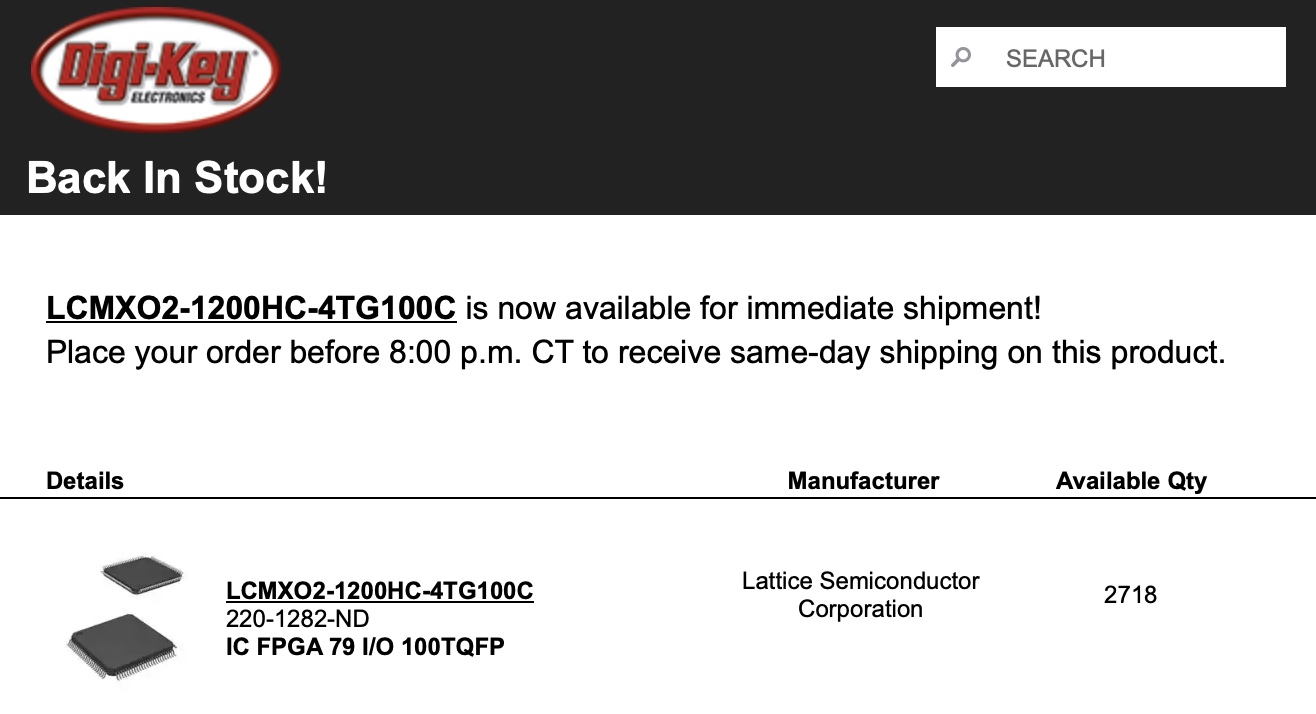

I’m happy to report that this storm is beginning to wind down, and the skies are clearing. Last week I received a long-awaited shipment of Xilinx XC9572XL chips for Floppy Emu that I’d ordered nine months ago, and today I received word from Digikey that the Lattice LCMXO2-1200 for Yellowstone is back in stock again after being completely unavailable everywhere for 1.5 years. The Atmel ATMEGA1284p for Floppy Emu isn’t generally in stock, but supplies are available directly from Microchip with “only” a few months’ delay on back-orders. It’s not a perfect situation, but it’s a huge improvement on a year ago.

The downside is that chip prices have increased substantially, especially for some of the older chips that I use. For that Xilinx chip specifically, the XC9572XL used to be around $2 each when purchased in large quantities, and now it’s $9.66 each with no quantity discounts available. Ouch!

Read 2 comments and join the conversationExtraterritorial Compliance and Small Business

I’m a tiny business selling physical products through a web store to a global audience. I face a pile of business-related regulatory compliance requirements from my local city, county, state, and national government. A recent trend has seen the unwelcome addition of new compliance requirements from states and countries where I don’t live and don’t have any physical business assets – extraterritorial laws and regulations designed to reach beyond the borders of the governments that created them. While most of these regulations are well-meaning, there’s a very large combined burden from regulations from dozens of states and countries around the world where customers exist. For a small business, it means ever more time spent pushing paper, and less time focused on the core business and product development. Ultimately it could force the difficult choice to stop serving customers outside the home area.

Extraterritorial Regulations Background

For many US-based businesses, the European GDPR regulations were their first experience with an extraterritorial law. This EU regulation is mostly responsible for the proliferation of “cookie warnings” we see on virtually every web site today, regardless of whether the site’s owner is located in the EU. In this case, the EU asserts jurisdiction over companies anywhere that may interact with EU citizens on the web. Unless the web site uses geolocation to block visitors from Europe, this means GDPR is effectively a global regulation.

How are these extraterritorial laws enforced? The EU doesn’t have any legal jurisdiction over people outside its borders, and no standard way to enforce its extraterritorial regulations. Enforcement relies on the high amount of international business interconnections in today’s world. Non-EU companies that violate GDPR may have their EU-based shipments and assets seized, or they may be ostracized by forbidding EU companies from doing business with them. Only the most insular companies can afford to ignore such threats.

Just in case it’s not clear, I’m not a huge fan of extraterritorial regulations. They not only make BMOW’s operations more difficult, but they subject people to regulations where they had no representation in the decision making. But I do acknowledge something is needed to craft sensible laws in a cloud-based world where location can be a fuzzy concept.

EU Requirements

From BMOW’s viewpoint, many of these externally-imposed regulations are coming from the EU.

LUCID is an obligatory packaging requirement. As best as I can understand, it exists in many EU countries but the enforcement effort is from Germany. All companies, wherever they’re located, are required to register themselves with the LUCID authorities and declare their annual weight of shipped packages. Then they must purchase a packaging license from a third party. The cost of this license is intended to offset the cost of disposing of or recycling the packaging from shipments, and it depends on the type of packaging used (for example paper versus plastic) as well as the total amount. The goal is to encourage companies to use more environmentally-friendly packaging options, which is laudable. But for businesses outside the EU, the implementation is onerous and it creates an extra hoop that must be jumped through for every international sale.

Language and product support requirements for other countries have also been a challenge and a source of confusion. I once had a shipment rejected by the German customs authority for reasons that weren’t immediately clear. After speaking with the customer, who spoke with the customs inspector, I was informed that I needed to provide German language product documentation and an in-country representative to handle product concerns. The customer didn’t get their package, and I had to apologize and give a refund. I’d never heard of that requirement before, nor has it come up again since then.

Another potential source of externally-imposed regulation is the GDPR. Beyond the actual privacy requirements that were already mentioned, businesses that do not have a physical presence in any EU country may need to have a physical representative located inside the region to comply with the GDPR.

Sales Tax Collection

Tax collection is the most visible area where other states and countries impose requirements on businesses outside their borders. For internet-based sellers in the USA, it used to be common practice to collect sales tax from customers located in the same state as the business, and everyone else got tax-free purchases. If a customer in New York bought something from an internet merchant in California, the customer was supposed to file and pay a New York use tax return, but in reality zero people did this and New York would just lose the tax revenue. In recent years the states have been much more aggressive about pursuing sales tax from out-of-state business, based on confusing requirements about economic nexus. For sales within the USA, businesses may have to collect sales (at varying location-based rates) and submit separate sales tax returns to up to 45 different states, individually.

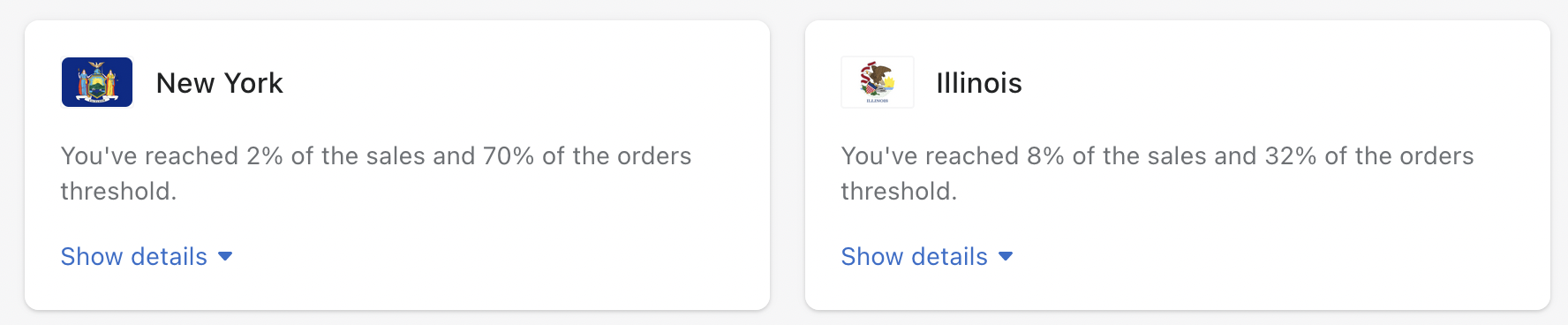

Most states now apply a sales threshold beyond which out-of-state sellers are required to collect and report sales tax, even if they don’t have a physical presence in the state. Some e-commerce platforms like Shopify will track these thresholds for you. Here’s some of mine:

Unfortunately the automated tracking of a sales threshold is a completely different animal from actually registering with a state’s tax authority and filing a quarterly sales tax return. California’s sales tax return already requires several hours of my time four times per year, and I don’t relish the thought of adding returns in New York and Illinois and 42 other states. I’m undecided about what I’ll do when that New York threshold reaches 100 percent. Cutting off sales to customers in New York isn’t a fun prospect, but neither is adding more compliance paperwork to an already full pile.

VAT Collection

Just as New York and Illinois are eager to get sales tax when their residents buy something from my California business, France and Germany are eager to get VAT when their residents buy something from my USA business. Now it’s called VAT instead of sales tax, but it’s the same concept and it extends the potential tax collection and reporting burden from 45 US states to every nation in the world.

Currently it’s the EU and Canada at the forefront of international VAT collection efforts. And unlike for out-of-state US sales tax, there’s generally no sales threshold and no minimum purchase amount below which small businesses can take shelter. EU countries require that non-EU businesses collect and submit VAT beginning with their very first sale, for any amount of dollars or euros. It’s totally understandable that these countries want to recoup the lost VAT revenue, but it puts a huge amount of extra compliance burden on small businesses. The idea of registering with tax authorities in Belgium, collecting per-customer VAT payments, and submitting periodic European tax returns and reports… for me, as a company with no EU business presence, that’s simply a bridge too far.

Fortunately there’s an alternative that works for now. BMOW can send shipments to the EU and Canada without any VAT, and the authorities in those countries will collect the VAT directly from the customer before delivering the shipment. It sounds great, except it creates some extra delays and costs for customers in those locations. Even when everything goes as expected, it’s a cumbersome process where the package gets stored in a warehouse while the shipper sends a notice to the customer, asking for the payment of VAT plus an additional brokerage fee. The customer may be able to pay online, or may need to physically visit a post office or shipping office. Once the VAT is paid, the package gets released for final delivery to the customer’s door. But if there’s a hiccup in the process, the customer never gets notified that their package is awaiting VAT payment. It languishes in a warehouse for weeks until it’s finally returned to sender by the slowest possible method, arriving back at my address six months or a year later.

So What?

There’s a lot of regulation that impacts small businesses, and much of it from external authorities, but so what? I expect this essay may attract some negative comments and a story on Hacker News titled Small Business Snowflake Thinks Laws Shouldn’t Apply to Him. They’ll say “If you don’t like the laws in (wherever), then don’t serve customers there!” Quite right. And that’s exactly the decision I’m facing now.

I’m realistic. The tax man needs to get paid, and can’t allow buyers to escape paying tax by purchasing everything out-of-state or out-of-country. Governments need to be able to craft product environmental and safety laws that won’t be trivially circumvented by products coming from outside their borders. These are real problems.

But where does this leave a small business with a global reach, a 1.5-person show selling retrocomputer gadgets that were designed for fun? Every day I’m looking at the mounting pile of compliance requirements and paperwork coming from every corner of the globe, and wondering how I’ll ever find time for business and product development amid everything else. My local and state compliance requirements already include the city business license, state reseller permit and sales tax returns, income tax returns, liability insurance, worker’s comp, employment regulations, and more. It’s already a mountain of red tape, even before external jurisdictions begin to impose their own requirements on me.

Ultimately my hope is to pay somebody to handle most of this stuff, if it’s not prohibitively expensive. I don’t spend time stressing about payroll filings, because I use a payroll service. Maybe an accountant to handle the 50 different sales tax and VAT reports? For several of these requirements like LUCID and EU VAT, there already exist cottage industries of in-country agents that will assist foreign businesses. Shopify has some support for these things too, although they tend to be focused on collecting information and stop short of actually fulfilling the compliance obligations. When I researched them in the past, my eyes quickly glazed over with legalese and I failed to grasp the big picture of what exactly I’ll need to do. But with a bit of luck, I hope to reach the summit of this regulatory compliance mountain.

In my dream world, the US would have a single national sales tax system instead of countless separate state, county, and city tax fiefdoms. Then governments wouldn’t worry about losing revenue on out-of-state sales, while businesses would only have to cope with a single collection and reporting system, and everyone would benefit. In this dream world, countries would also work together at the UN or WTO to draft product requirements that applied consistently across the globe, instead of a hodge-podge of different requirements in every different country. Compliance and reporting requirements would also come with intelligent thresholds based on sales volume or business size, to ensure that the compliance burden was appropriate for the business size, and nobody was driven out of business due to overwhelming red tape. I can dream.

Read 6 comments and join the conversationSemiconductor Shortage and Business Threat

I’ve written several times about the global semiconductor shortage and the difficulty of getting parts. This has been a problem for everyone since COVID hit, but a year ago I’d hoped things would be improving by fall 2022. Unfortunately it’s worse than ever. It’s now looking increasingly likely that I’ll need to cease most production sometime in 2023, sell off the remaining stock of hardware, shut down the BMOW business, and ride off into the sunset to do something else.

Is it really that bad? In the pre-COVID days, I could just buy thousands of parts from Digikey or Mouser whenever I needed them. More recently I’ve had to place orders for chips 3-4 months in advance, which requires more upfront planning but is still doable. But now several key chips for Floppy Emu and Yellowstone just aren’t available with any realistic lead-time. Suppliers are quoting dates in 2024, or just declining to give any dates at all. Yellowstone has been in this zone for a while, but now Floppy Emu is falling into the same trouble, and without those two products I really don’t have a business.

Yellowstone uses a Lattice FPGA that was widely available when I designed the board, but has since become unobtanium. Officially they’re still quoting delivery dates in late 2023, but the dates keep moving back. I strongly suspect that the dates are based on nothing more than hopes and prayers. A few days ago I received an unexpected email from Mouser, telling me that the FPGA was now back in stock and available to order. But I checked the site, and it still showed zero stock and a year+ lead time. A Mouser rep confirmed this was an error. Ugh.

For the Floppy Emu, microcontrollers from Atmel (now Microchip) have been harder and harder to find. But at least the lead times are somewhat manageable, currently about 4 months, and so far they seem to be hitting those dates. The biggest challenge is the CPLD from Xilinx (now AMD), which isn’t available from any official supplier and where reliable delivery dates are scarce. I had some Xilinx parts on order from Mouser with an expected delivery date of January 2023, then I received notice today that the delivery date has been pushed out to January 2024. Say what?

Some of these parts may be available from third-party suppliers, but I hate dealing with these guys. The whole surplus parts industry seems built on a foundation of deception and lies. Some of them will give an upfront quote if you ask nicely, but many use a retroactive repricing approach that drives me bananas. They might advertise having 37957 parts in stock with a price of $6.02 each, but the fine print says “Due to the shortage of the global supplier, some products may rise in price and out of stock. We will manually confirm after placing the order.” So I place an order and pay for it, then 24 hours I get an email saying sorry we only have 233 parts and the price is $25.44 each. If I decline, then they (eventually) refund me, but it’s a huge waste of time and a terrible way to do business. Even if I can get the parts, I’ll pay through the nose and my retail product prices will surely need to increase.

I’m afraid it’s a gloomy forecast. I’ll keep scrounging for parts as long as I can, and hope that this shortage eases soon.

Read 15 comments and join the conversationUPS International Shipping Redlining in South San Francisco

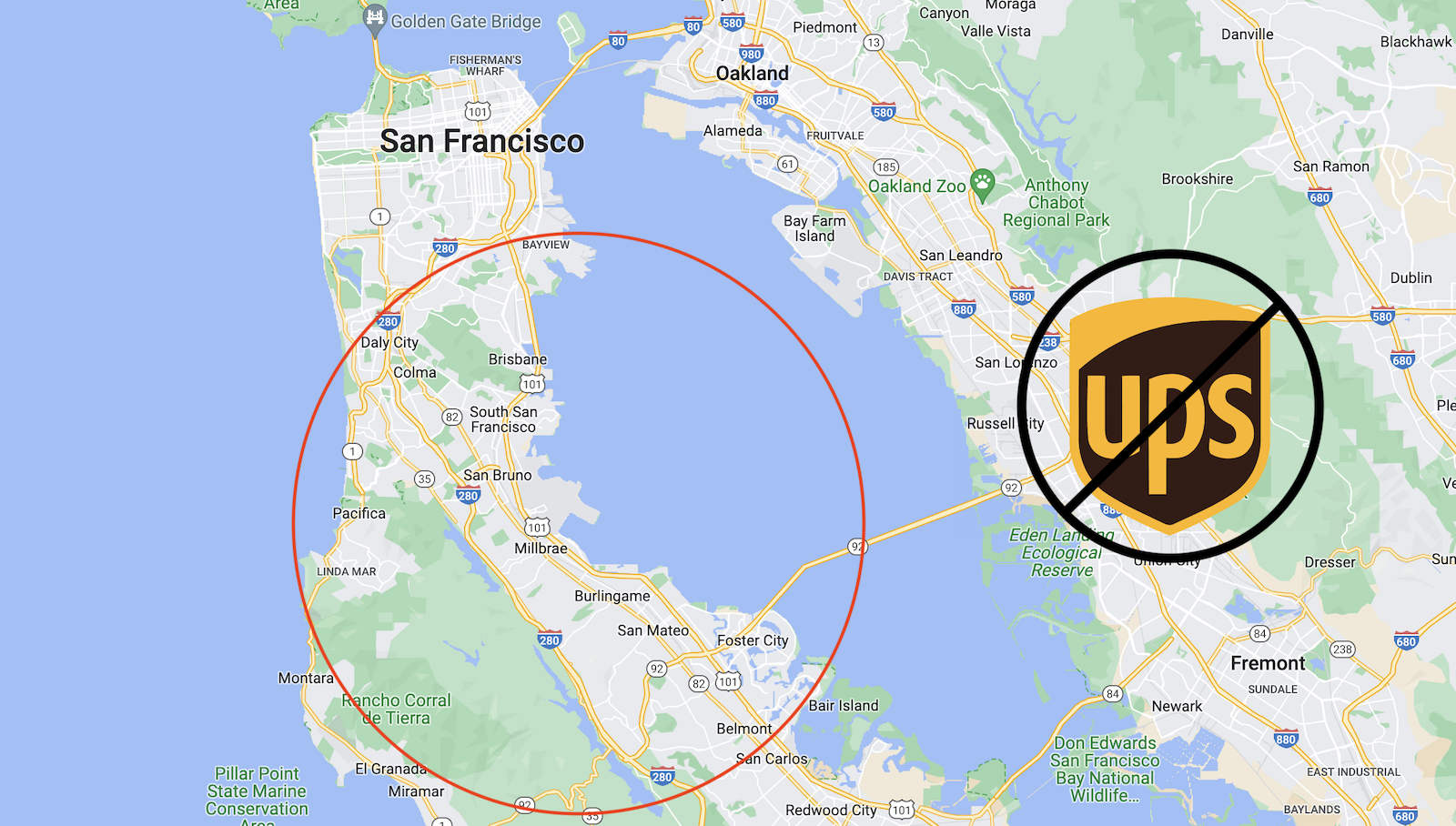

I’ve stumbled across a puzzling mystery. If you live in the southern part of the city of San Francisco, or in a large area further south into San Mateo County, UPS will not sell you international shipping labels. But change your Ship From zip code to a different city just a few miles away, and UPS will be happy to quote you for international shipping. I reached this conclusion after spending many hours pricing dummy international shipments with different Ship From and Ship To addresses, package sizes and weights, and content types. Only the Ship From address seems relevant. A UPS agent confirmed this behavior but couldn’t offer any explanation or solution.

I first discovered this problem on April 4, while using the third-party shipping service Pirate Ship to generate some UPS international shipping labels. For all my packages, Pirate Ship offered US Post Office shipping options, but nothing from UPS. After several hours working with Pirate Ship’s tech support, they concluded UPS was declining international shipping service to this region for some unknown reason. They told me to take up the issue with UPS.

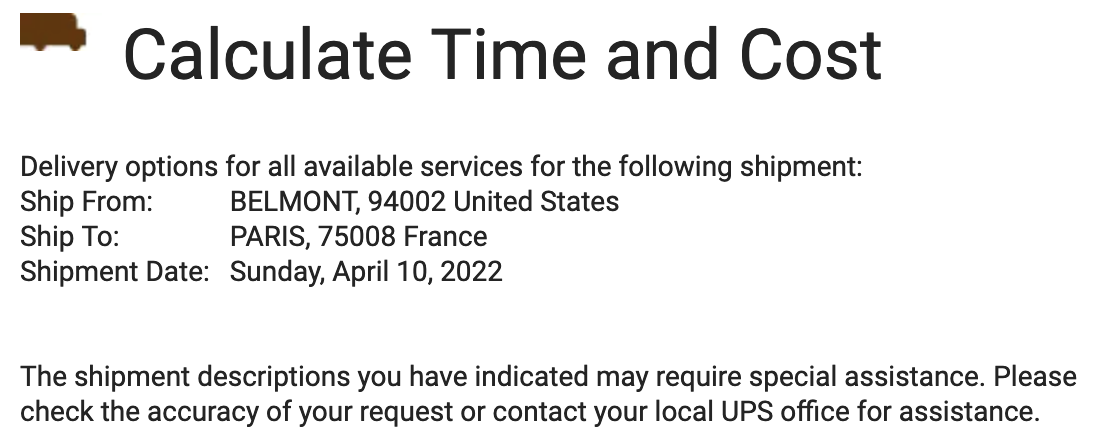

Initially I didn’t believe Pirate Ship’s explanation, but then I discovered I could reproduce the same problem directly at the UPS.com page for international shipping quotes. You can try this too. Go to the UPS international shipment cost calculator page, as a guest (not logged in). Enter these package details:

Ship From: United States, Redwood City, zip code 94065. Or mostly anywhere else in the United States, except one of the redlined areas listed below.

Ship To: France, postal code 75008, Paris. Or try any another major city in Europe, Asia, wherever, it doesn’t matter.

Customs Value: 119

Package Details: My packaging, 11 x 9 x 2 inches, 0.8 pounds, 119 dollar value

You’ll see a list of available UPS shipping methods with specific price quotes. For example, UPS Worldwide Expedited service costs $154.44 to Paris. You’ll get the same behavior with Ship From addresses in most parts of California or elsewhere in the United States.

Now try the same experiment again, but for the Ship From location, choose one of the following cities and zip codes. These cities are a contiguous geographic region just south of San Francisco, centered around the San Francisco airport. The total population is about 1 million people.

94002 Belmont

94403 San Mateo

94402 San Mateo

94401 San Mateo

94404 Foster City

94010 Burlingame

94030 Millbrae

94128 San Francisco

94112 San Francisco

94132 San Francisco

94066 San Bruno

94080 South San Francisco

94019 Half Moon Bay

94044 Pacifica

94015 Daly City

94005 Brisbane

When you repeat the test using one of these Ship From addresses, UPS.com complains:

The shipment descriptions you have indicated may require special assistance. Please check the accuracy of your request or contact your local UPS office for assistance.

This is consistent with the apparent UPS international shipping redlining that I observed when using Pirate Ship. I spoke with the staff at the local UPS Store, but they’d never heard of this problem, and said their outgoing international shipments were working just fine. Through trial and error, I discovered that Shopify Shipping isn’t affected by this problem either, so it may have something to do with the class of UPS shipping account used to buy shipping labels. The problem definitely affects Pirate Ship, UPS.com’s own shipping quote system, and probably others too.

I then spent a long time on the phone with other UPS support agents who told me I was wrong, and that the Ship From zip code didn’t matter for determining international shipping service availability. On the third try, I was finally able to demonstrate the problem to a UPS agent, but she could only say “I don’t know why it’s doing that”. She couldn’t offer any explanation or solution. That was several days ago, and the problem is still happening today.

Read 5 comments and join the conversationBMOW Business Update – Good, Bad, and Scary

It’s been a while since I last shared any business updates for BMOW. The past few years have been an exciting trip, as my personal technology blog has grown into a side hustle and then into a bona fide business. Initially BMOW was something I did in my spare time away from my real job (video game development), then it was something I did while I was between jobs, and now for the past few years it has been my real job. The experience has been great, but now the global chip shortage has scrambled everything, and the future outlook is growing scary.

The Good

First the good news. The gradual transformation from blog to store began in 2014, when a few blog readers started asking to buy the Macintosh floppy disk emulator that I’d been writing about. I sold about $18000 of hardware that first year, doing all the assembly and fulfillment by hand. It didn’t leave a huge profit after subtracting all the cost of parts, tools, and other business expenses, but it was a thrill to be making something that people wanted.

In the time since then, sales have grown consistently every year. I’ve moved the assembly work to dedicated manufacturing partners, added many new products to the BMOW line-up, and even hired a part-time employee to help with order fulfillment and customer support. In 2021 I sold several thousand Floppy Emus, plus lots of other products too, which was amazing. Gross revenue was into the hundreds of thousands. My net income after all expenses is less than I could earn as a software developer here in Silicon Valley, but it’s still a respectable number, and being my own boss is fantastic. I couldn’t imagine going back to a regular full-time job now. Sure, I’m always complaining about the challenges of international shipping or payment processing disasters or something else, but that comes with the territory of running my own business.

The Bad

If there’s anything bad here, it’s the overall fragility of the business. A great business would have revenue from many diverse products, with reliable sources of supply, and a large and growing market. I have none of that. The market is owners of obsolete computers from 25+ years ago. There simply aren’t many of those, and the number is shrinking every year as some computers break and can’t be repaired. How many working Apple II and classic Macintosh systems even exist today? Ten thousand? Ten million? I really don’t know. I keep thinking that I must have saturated the market already, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Product diversity is another weak point. BMOW sells eighteen different products, but 80 percent of revenue comes from the Floppy Emu Disk Emulator. Everything else is basically just a distraction. If anything threatens the supply or sales of Floppy Emus, then the business is in big trouble.

The Scary

Friends, the global chip shortage is very bad. For over a year columnists keep predicting it will get better soon, but it only gets worse and worse. This won’t continue forever, but how much longer will we have to endure this crunch? Six months? A year? Two, or three? And what will the landscape look like then? Will semiconductor makers take this opportunity to discontinue some of their oldest and least-profitable chips, the chips that are needed for vintage computer hardware?

The Floppy Emu uses two primary chips: a microcontroller and a programmable logic device. The mcu is an Atmel ATMEGA1284 and the logic device is a Xilinx XC9572XL. Both are relatively old technology, like 15+ years old. Both have seen their prices double or triple in the past couple of years. And both now have very limited or zero stock everywhere, with little hope of getting more stock anytime soon. Maybe I can get more in six months, or a year? Maybe never?

The last time I did a Floppy Emu manufacturing run, it was very difficult to find parts, particularly the ATMEGA1284. I almost gave up. My manufacturing partner made a lot of calls, and eventually found a surplus parts broker who could fill the order for a nosebleed price. As of today, I have enough finished Floppy Emus to last until roughly September at my normal rate of sales. I don’t know what happens after that. If I can’t find the required parts, or redesign the board around new parts, then I’m basically out of business.

Strategizing

What would you do in this situation? I can’t decide, and I’m spinning my wheels trying to decide what to do, while the clock is ticking and time is running out.

One option is to redesign the Floppy Emu hardware around new parts with better availability. The existing parts are pretty old anyway, so a refresh would make sense. But what new parts should I choose? It’s not just the ATMEGA1284 that has supply problems – it’s virtually all microcontrollers from Microchip, ST, TI, everybody. And the options for programmable logic parts are even worse. There’s very scarce availability of any programmable logic parts, and the few that are available are actually less capable than the old Xilinx part, or cost five times as much. Sure, you can sometimes find parts with a few hundred at one supplier and 1000 at another, but it’s usually one specific oddball package or variant while the rest of the family is out of stock. That’s a fluke, not a reliable supply. To feel comfortable betting the farm on a new chip, I’d want to see all the members of its family with deep stock in the many thousands, at multiple suppliers.

If I redesign the Floppy Emu hardware, should I redesign around the best available parts options today, or around a blue-sky vision of the best-suited parts for the task regardless of current availability? A redesign will be a major time-consuming effort, and I can’t afford to get it wrong. It’s a gamble. If I redesign around the best available parts today, that greatly limits my choices. I could be locked into sub-optimal parts for a long time to come. That might make it much harder to add new features, or might create new supply problems in the future, or increase my costs. If I redesign around the parts I’d like to use in a perfect world, then I could have to wait a very long time before they become available again. The redesigned hardware might never see the light of day except for a few prototype units.

Given how much time any redesign would require, and the uncertain results, there’s another option I’m seriously considering: do nothing. Place some back-orders now for the ATMEGA1284 and XC9572XL, and then forget about it. Use the coming months to work on Yellowstone features or develop some cool new product, instead of redesigning the Floppy Emu. Hope that the parts become available before I need them, and if they don’t, it will be lean times at BMOW. I would still probably want to revisit the Floppy Emu hardware design in another year or two, to take advantage of the capabilities of newer parts, but I would do it after the chip shortage is over and there’s a clearer picture of what parts I can safely bet on.

Read 15 comments and join the conversation