Happy Birthday BMOW!

Yesterday was the 1 year anniversary of the first BMOW journal entry, which described the CPU architecture design that I’d worked out on paper. The planning phase grew from there, and lasted several months. The first wires in what would become BMOW weren’t connected until March 9, but it was only a month more past then until the first successful run of a fibonacci program on the hardware. I guess planning pays off!

Read 2 comments and join the conversationBASIC?

I’ve started looking at getting BASIC working on the machine. At first I thought I might need to reverse engineer an existing 8-bit BASIC from the ROM image, or write my own, but then I found something much better. These guys have reverse-engineered 7 different versions of Microsoft BASIC, creating a set of well-documented 6502 assembly source files. It’s probably nearly as good as the original source was, and you can conditionally compile Applesoft, Commodore, and other BASIC variants.

I’ve been working on this for 4 days now, and it’s going fairly well. Early on, I found that quite of few of BMOW’s instructions that are supposed to act like 6502’s aren’t quite accurate in the way they update the condition codes. Some 6502 instructions update only the negative and zero flags, others updates those plus the carry and overflow flags, and still others update additional combinations of flags. In contrast, most BMOW instructions either updated all the flags, or none. Fixing the behavior to match the 6502 required a lot of new microcode and a couple of wiring changes.

There are also quite a few 6502 instructions that I just never bothered to implement in BMOW, because I didn’t find them useful. Microsoft BASIC uses practically every possible instruction, though, so I’ve been madly implementing new instructions in microcode, updating the assembler and simulator to match.

I think it’s actually getting close to working. Running in the simulator, BASIC detects how much RAM I have, prints a copyright message, and dumps me to the BASIC prompt. But if I type something like “10 PRINT ‘Steve’ “, it spews an error that’s every possible BASIC error message concatenated together. The line that reports the number of bytes free also shows it as something like “19019.1901 bytes free”. Strangely, it actually converts the byte count to a floating point number, then calls the floating point print routine, and something’s clearly going wrong inside there. I haven’t actually tried running on the real hardware yet, but if I can get the major issues sorted out in the simulator, it should go pretty smoothly.

Read 9 comments and join the conversationMicrochess Video Support

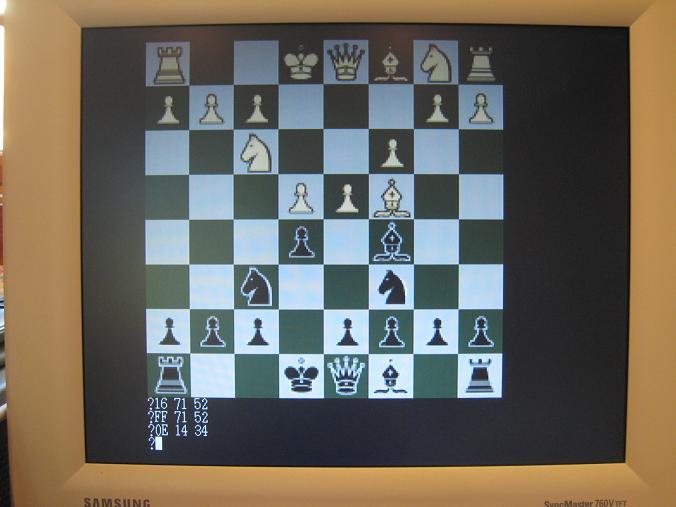

Microchess for BMOW is now a full-fledged graphical program, instead of a text-mode program using ASCII art for the board. It was pretty easy to do, fortunately. I wrote a stand-alone routine to draw the board graphics using the existing Microchess board state in memory, and replaced the ASCII art code with a call to my new routine. It uses BMOW’s mixed-video mode capabilities, with a 208×208 board using 16 colors, a 4-line scrolling text area for move entry, and an empty 48×208 area to the right of the board. Maybe this area could be used to show a running list of moves?

Simulator Download

I’ve beefed up the BMOW simulator in a major way, and it’s starting to look pretty good! For the curious, you can grab the latest simulator here, and give it a try yourself. I’ve bundled it with the Microchess program binary, as well as Wozniak’s Apple II monitor binary. The BMOW simulator is a Windows program, and requires the .NET Framework 2.0 runtime, which you probably already have installed on your PC. If not, you can download it from Microsoft.

The software simulates BMOW’s behavior at the hardware level, all the way down to the microcode, so it’s a very faithful reproduction of the real machine’s behavior. On an older 2.4GHz Athlon CPU, the simulation runs about as fast as the real BMOW hardware with its 2MHz CPU clock. The simulator shows the state of all the BMOW registers, condition codes, and the contents of main memory. It also simulates BMOW’s LCD panel and video display (text mode only). The standard debug stepping controls are all provided: run, pause, step over, step in, step out, and microinstruction step. Source is displayed for the current instruction and microinstruction. Instruction source can be displayed using the original commented assembly listing if a symbol file is available, or using a disassembly of the contents of memory. Breakpoints can be set or cleared by clicking on a line in the source window.

Here’s the BMOW simulator running Microchess:

To load a different program file, choose “Open Program File…” from the menu, and choose one of the provided .bin files. Press the green arrow button to start the simulator running, and the red pause button to pause it. While the simulator is running, you can type at your PC’s keyboard, and your key input will be passed to the running BMOW simulation. Some of the controls like the memory view only work when the simulation is paused.

Microchess Instructions

- C – Clear and reset the board. Computer plays white, you play black.

- P – Tell the computer to play its move. **** will be displayed while it thinks.

- 6343[Return] – Move your piece from square 63 to square 43. The board will be redrawn after each keypress.

- See the Microchess manual for more details.

BMOW/Apple II Monitor Instructions

- 1234 – Display the contents of memory location $1234 in the current bank.

- 1234.1237 – Display the contents of memory locations $1234-$1237 in the current bank.

- [Return] – Display the values in up to eight locations following the last displayed location.

- 12K – Set the current bank to $12.

- 1234:1F 83 BC … – Store the values in consecutive locations starting at $1234 in the current bank.

- :1F 83 BC … – Store the values in consecutive locations starting at the next changeable location in the current bank.

- 1234<AB00.AB82M – Move (copy) the values in the range $AB00-$AB82 into the range beginning at $1234 in the current bank.

- 1234<AB00.AB82V – Verify (compare) the values in the range $AB00-$AB82 to those in the range beginning at $1234 in the current bank.

- 1234L – List (disassemble) 20 instructions starting at $001234. Subsequent L’s will display 20 more instructions each. Disassembly currently only works in bank 0.

- 1234G – (Go) Transfers control to the program beginning at $001234. Go currently only works in bank 0.

- More Apple II monitor commands that may or may not work in the BMOW version are described in this Apple II summary.

You might wonder why both of the provided programs start at address $010002. The real BMOW hardware contains the boot loader in bank 0, at addresses $000000-$00FFFF. The boot loader loads the program binary into bank 1, addresses $010000-$01FFFF. Addresses $010000-$010001 are used as a counter while loading the program data, so the program itself begins at $010002. The simulator skips this boot loader step, and starts running directly at $010002.

Read 4 comments and join the conversationMicrochess

Holy cow, BMOW runs actual software! In this case it’s Microchess, a 1 kilobyte marvel from 1976. Here it is, showing the first few moves of the Giuco Piano opening:

The two-letter code for each piece indicates the color and type. For unknown reasons, “C” means rook (castle?) and “R” means knight. The three hex bytes at the bottom show the piece ID and start and end positions for the most recent move.

The original Microchess was written by Peter Jennings in 1976, and was one of the earliest examples of commercial software. It targeted the KIM-1, a 6502-based hobbyist computer whose only output was a six-character hex LED display. Those three hex bytes in the screenshot were the entire output of that original KIM-1 version. The text-based chess board was added later to support more capable computers with video displays. Amazingly, the entire Microchess program is just 924 bytes. Allowing a few dozen more bytes for runtime memory needs, it still fits in one kilobyte. Good luck writing a functional chess program in 1K on a modern PC!

Porting Microchess to BMOW was fairly painless. It’s written in 6502 assembly, and BMOW’s instruction set is an imperfect 6502 superset, so there wasn’t much work to do there. The I/O routines were already separated from the rest of the code, so I only needed to point them at the existing keyboard and video I/O routines in BMOW’s ROM to finish the job.

There are still some bugs to work out. BMOW Microchess does make legal moves, but they’re not always very sensible. I wasn’t expecting top-quality chess play, but it often seems to not realize that a piece is at risk of capture. I was able to easily capture a bishop and queen, without it making any attempt to defend them. Hopefully after I dig into the Microchess code further, I can determine if it’s a bug related to BMOW’s imperfect emulation of 6502 behavior, or something else. Meanwhile, back to chess!

Read 3 comments and join the conversationEverything But The Kitchen VSYNC

I’ve decided to do whatever it takes to fix the VSYNC problem with BMOW’s video, and right now it looks like that means ripping out and redesigning a decent portion of the video address circuitry. Things are fine when displaying a static image, but not when the image is changing. When trying to animate something, or scroll a screenful of text, the VSYNC signal often gets fubared. This causes the monitor to throw up its hands and go into power-saving mode. It takes about 5 seconds for it to come back again after VSYNC stabilizes, and the constant pattern of scroll, lose sync, wait, regain sync is infuriating.

I did quite a bit of investigation of the problem using the oscilloscope. The proximate cause is that a miscount occurs in the GAL named VERTHI, which maintains the upper 5 bits of the row count. The low 4 bits of the row count and the 9 bits of column count are all fine. I can’t say why VERTHI is going wrong, but it’s presumably something related to noise or a race condition. There is a fair bit of noise observed with the scope. I tried rewiring the clock wires using a few different topologies in an attempt to reduce noise, without success. I also tried two more completely different clock sources for the row counter: the inverted high bit of the column count, and the HBLANK signal. HBLANK introduced some other timing problems but didn’t help with the loss of sync. The high bit of the column count made the loss of sync far worse. I also tried replacing the GAL with another one, and replacing the other parts that send signals to the GAL.

I wish I had a better explanation, but at this point I’m convinced I just shouldn’t use a GAL for the row counter. Instead I’m planning to use a regular hardware counter like a few 74163s or 74393s, and use the GAL to buffer the row address and generate VSYNC and other derived timing signals. Unfortunately that means eating up more of what little board space is left, dimming the prospects for a future audio system. It also means ripping out gobs of my painstakingly-wrapped wires and replacing them with new ones. I just hope it actually fixes the problem!

Read 17 comments and join the conversation