A Handmade Executable File

Make a Windows program by stuffing bytes into a buffer and writing it to disk: no compiler, no assembler, no linker, no nothing! It was the obvious conclusion of my recent efforts to gain more control over what goes into my executables, and this time I could set every bit exactly as I wanted it. Yes, I am still a control freak.

I began with a simple C program called ExeBuilder to construct the buffer and write it to disk in a file named handmade.exe. ExeBuilder looks like this:

#include "stdafx.h"

#include <Windows.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

HANDLE hFile = CreateFile("handmade.exe", GENERIC_WRITE, 0, NULL, CREATE_ALWAYS,

FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL, NULL);

BYTE* buf = (BYTE*) HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, 1024);

DWORD exeSize = BuildExe(buf);

DWORD numberOfBytesWritten;

WriteFile(hFile, buf, exeSize, &numberOfBytesWritten, NULL);

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), 0, buf);

CloseHandle(hFile);

printf("wrote handmade.exe\n");

return 0;

}

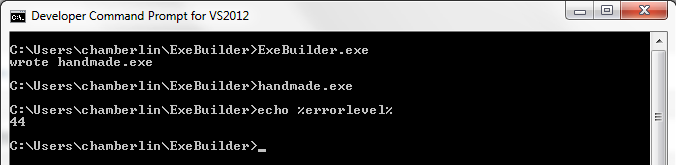

All of the interesting work happens in BuildExe(). This function manually constructs a valid Windows PE header, filling the required header fields and leaving the optional ones zeroed, then creates a single .text section and fills it with a few bytes of program code. The program in this case doesn’t do much – it just returns the number 44.

Sorting out the PE header details and determining which fields were actually required was a chore. All my testing was performed under Windows 7 64-bit edition. If you try these examples on your PC, it appears that earlier versions of Windows were more permissive with PE headers, while Windows 8 and 10 may be more strict about empty PE fields.

Here’s my first implementation of BuildExe(), which makes a nice standard executable with a single .text section containing 4 bytes of code.

inline void setbyte(BYTE* pBuf, DWORD off, BYTE val) { pBuf[off] = val; }

inline void setword(BYTE* pBuf, DWORD off, WORD val) { *(WORD*)(&pBuf[off]) = val; }

inline void setdword(BYTE* pBuf, DWORD off, DWORD val) { *(DWORD*)(&pBuf[off]) = val; }

inline void setstring(BYTE* pBuf, DWORD off, char* val) { lstrcpy((char*)&pBuf[off], val); }

DWORD BuildExe(BYTE* exe)

{

// 1. DOS HEADER, 64 bytes

setstring(exe, 0, "MZ"); // DOS header signature is 'MZ'

setdword(exe, 60, 64); // DOS e_lfanew field gives the file offset to the PE header

// 2. PE HEADER, at offset DOS.e_lfanew, 24 bytes

setstring(exe, 64, "PE"); // PE header signature is 'PE\0\0'

setword(exe, 68, 0x14C); // PE.Machine = IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386

setword(exe, 70, 1); // PE.NumberOfSections = 1

setword(exe, 84, 208); // PE.SizeOfOptionalHeader = offset between the optional header and the section table

setword(exe, 86, 0x103); // PE.Characteristics = IMAGE_FILE_32BIT_MACHINE | IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE | IMAGE_FILE_RELOCS_STRIPPED

// 3. OPTIONAL HEADER, follows PE header, 96 bytes

setword(exe, 88, 0x10B); // Optional header signature is 10B

setdword(exe, 104, 4096); // Opt.AddressOfEntryPoint = RVA where code execution should begin

setdword(exe, 116, 0x400000); // Opt.ImageBase = base address at which to load the program, 0x400000 is standard

setdword(exe, 120, 4096); // Opt.SectionAlignment = alignment of section in memory at run-time, 4096 is standard

setdword(exe, 124, 512); // Opt.FileAlignment = alignment of sections in file, 512 is standard

setword(exe, 136, 4); // Opt.MajorSubsystemVersion = minimum OS version required to run this program

setdword(exe, 144, 4096*2); // Opt.SizeOfImage = total run-time memory size of all sections and headers

setdword(exe, 148, 512); // Opt.SizeOfHeaders = total file size of header info before the first section

setword(exe, 156, 3); // Opt.Subsystem = IMAGE_SUBSYSTEM_WINDOWS_CUI, command-line program

setdword(exe, 180, 14); // Opt.NumberOfRvaAndSizes = number of data directories following

// 4. DATA DIRECTORIES, follows optional header, 8 bytes per directory

// offset and size for each directory is zero

// 5. SECTION TABLE, follows data directories, 40 bytes

setstring(exe, 296, ".text"); // name of 1st section

setdword(exe, 304, 4); // sectHdr.VirtualSize = size of the section in memory at run-time

setdword(exe, 308, 4096); // sectHdr.VirtualAddress = RVA for the section

setdword(exe, 312, 4); // sectHdr.SizeOfRawData = size of the section data in the file

setdword(exe, 316, 512); // sectHdr.PointerToRawData = file offset of this section's data

setdword(exe, 332, 0x60000020); // sectHdr.Characteristics = IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ | IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE | IMAGE_SCN_CNT_CODE

// 6. .TEXT SECTION, at sectHdr.PointerToRawData (aligned to Opt.FileAlignment)

setbyte(exe, 512, 0x6A); // PUSH

setbyte(exe, 513, 0x2C); // value to push

setbyte(exe, 514, 0x58); // POP EAX

setbyte(exe, 515, 0xC3); // RETN

return 516; // size of exe

}

The resulting file is 516 bytes. Check to make sure it works:

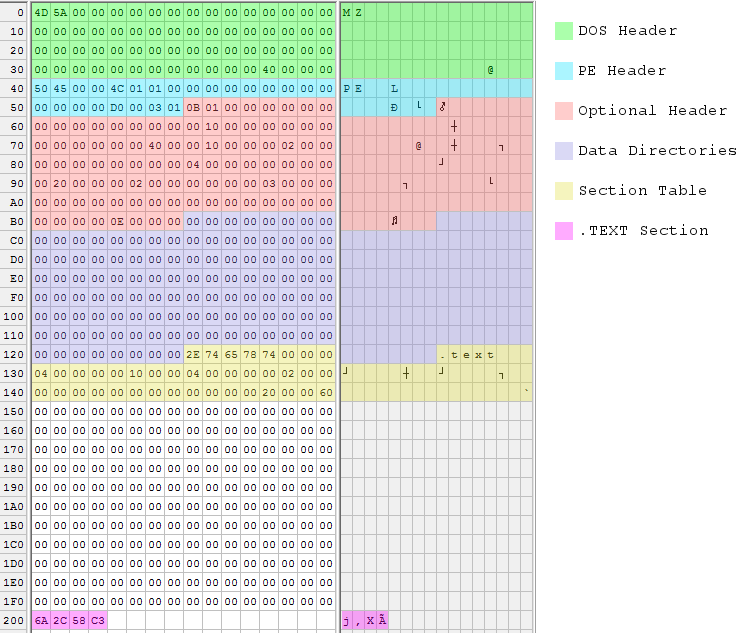

The executable is built from six data structures, which are numbered in the code’s comments. The cross-references in these structures are sometimes specified as offsets within the file, and sometimes as relative virtual addresses or RVAs. File offsets reflect the executable as it exists on disk, while RVAs reflect how it’s loaded in memory at run-time. An RVA is a run-time offset from the executable’s base address in memory. Getting these two confused will lead to problems!

DOS Header – The only fields that must be filled are the ‘MZ’ signature at the beginning and the e_lfanew parameter at the end (unless you’re actually writing a DOS program). e_lfanew gives the offset to the PE header, which in this case follows immediately after.

PE Header – The true PE header doesn’t contain much, because all the good stuff is in the optional header. The PE header specifies 1 section (the single .text section with the code to return 44), and 208 bytes combined size for the next two sections.

Optional Header – The optional header is only optional if you don’t care whether the program works. Some noteworthy values:

- SectionAlignment – Each section of the executable (.text, .data, etc) must be alignment to this boundary in memory at run-time. The standard is 4096 or 4K, the size of a single page of virtual memory.

- AddressOfEntryPoint – Program execution will begin at this memory offset from the base address. Because the section alignment is 4096, the program’s single .text section will be loaded at offset 4096, and execution should begin at the first byte of that section.

- FileAlignment – Similar to section alignment, but for the file on disk instead of the program in memory. The standard is 512 bytes, the size of a single disk sector.

- SizeOfHeaders – This isn’t really the combined size of all the headers, but rather the file offset to the first section’s data. Normally that’s the same as the combined size of all headers plus any necessary padding.

Data Directories – A typical executable would store offsets and sizes for its data directories here, the number of which is given in the optional header. Data directories are used to specify the program’s imports and exports, references to debug symbols, and other useful things. Manually constructing an import data directory is a bit complicated, so I didn’t do it. That’s why the program just returns 44 instead of doing something more interesting that would have required Win32 DLL imports. Handmade.exe does not have any data directories at all.

If you’re wondering why there are 14 data directories each with zero offset and size, instead of just specifying zero data directories, that’s a small mystery. According to tutorials I read, some parts of the OS will attempt to find info in data directories even if the number of data directories is zero. So the only safe way to have an empty data directory is to have a full table of offsets and sizes, all set to zero. However, I found other examples that did specify zero data directories and that reportedly worked fine. I didn’t look into the question any further, since it turned out not to matter anyway.

Section Table – For each section, there’s an entry here in the section table. Handmade.exe only has a single .text section, so there’s just one table entry. It gives the section size as 4 bytes, which is all that’s needed for the “return 44” code. The section will be loaded in memory at RVA 4096, which is also the program’s entry point.

Section Data – Finally comes the actual data of the .text section, which is x86 machine code. This is the meat of the program. The section data must be aligned to 512 bytes, so there’s some padding between the section table and start of the section data.

Here’s what dumpbin says about this handmade executable. Many of the fields are zero or have bogus values, but it doesn’t seem to matter:

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 11.00.50727.1

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Dump of file handmade.exe

PE signature found

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

FILE HEADER VALUES

14C machine (x86)

1 number of sections

0 time date stamp Wed Dec 31 16:00:00 1969

0 file pointer to symbol table

0 number of symbols

D0 size of optional header

103 characteristics

Relocations stripped

Executable

32 bit word machine

OPTIONAL HEADER VALUES

10B magic # (PE32)

0.00 linker version

0 size of code

0 size of initialized data

0 size of uninitialized data

1000 entry point (00401000)

0 base of code

0 base of data

400000 image base (00400000 to 00401FFF)

1000 section alignment

200 file alignment

0.00 operating system version

0.00 image version

4.00 subsystem version

0 Win32 version

2000 size of image

200 size of headers

0 checksum

3 subsystem (Windows CUI)

0 DLL characteristics

0 size of stack reserve

0 size of stack commit

0 size of heap reserve

0 size of heap commit

0 loader flags

E number of directories

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Export Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Import Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Resource Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Exception Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Certificates Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Base Relocation Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Debug Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Architecture Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Global Pointer Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Thread Storage Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Load Configuration Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Bound Import Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Import Address Table Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Delay Import Directory

SECTION HEADER #1

.text name

4 virtual size

1000 virtual address (00401000 to 00401003)

4 size of raw data

200 file pointer to raw data (00000200 to 00000203)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

60000020 flags

Code

Execute Read

Summary

1000 .text

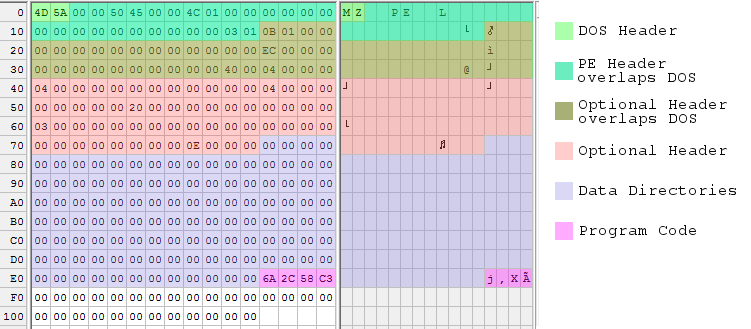

Sometimes a picture is worth 1000 words, so I also made a color-coded hex dump of the executable file:

Shrinking It

After doing all this, of course my first thought was to try making it smaller. There’s a lot of empty padding between the section table and the section data, due to the 512 byte alignment of sections in the file. There must be some way to shrink or eliminate that padding, right? I tried reducing Opt.FileAlignment to 4, moving the .TEXT section data down to 336, and adjusting sectHdr.PointerToRawData accordingly. All I got for my effort was an error complaining “handmade.exe is not a valid Win32 application.” I’m unsure why it didn’t work. Maybe the OS doesn’t like sections that aren’t 512 byte aligned in the file, no matter what the PE header says.

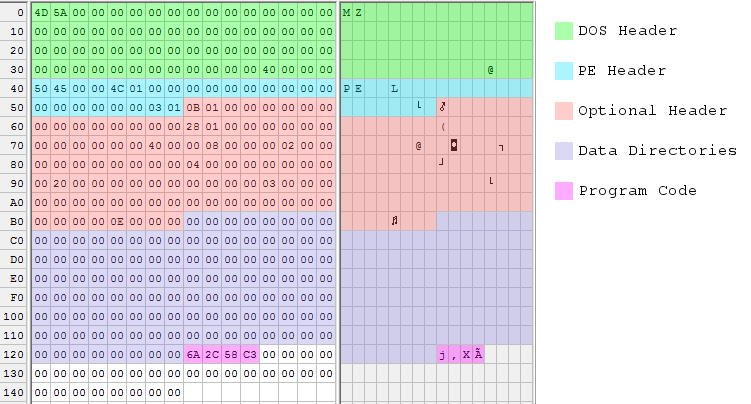

Then I thought maybe I could reuse the header as the section data. By changing sectHdr.PointerToRawData to 0, I could make the Windows loader use a copy of the executable header as the .TEXT section data. 0 is 512 byte aligned, so there wouldn’t be any alignment problems. It seemed strange, since an executable header is not x86 code, but by stuffing the 4 bytes of code into an unused area of the header and adjusting Opt.AddressOfEntryPoint, I could theoretically patch everything up. Lo and behold, it worked! The new executable was only 340 bytes.

With the 4 bytes of code now stored inside the header, I wondered if I really needed a section at all. The Windows loader will load the header into memory along with all the sections, so maybe I could just eliminate the .TEXT section completely, and rely on the entry point address to point the way to the code stored in the header?

This worked too, but not without a lot of futzing around. After setting PE.NumberOfSections to 0, PE.SizeOfOptionalHeader and Opt.SizeOfHeaders both had to be set to zero. They’re both essentially offsets to section structures, and with no sections, apparently a 0 offset is required. Opt.SectionAlignment also had to be reduced to 2048, and I honestly have no idea why. With those changes, the modified program worked.

With the elimination of the section table, this should have been enough to shrink the executable to 300 bytes, but I found that anything smaller than 328 bytes wouldn’t work. It appeared that the OS assumes a minimum size for the optional header or the data directories, regardless of the sizes specified in the header. So 28 bytes of padding are required at the end of handmade.exe. The 328 byte version of BuildExe() is shown here, with the changes from the previous version highlighted:

DWORD BuildExe(BYTE* exe)

{

// 1. DOS HEADER, 64 bytes

setstring(exe, 0, "MZ"); // DOS header signature is 'MZ'

setdword(exe, 60, 64); // DOS e_lfanew field gives the file offset to the PE header

// 2. PE HEADER, at offset DOS.e_lfanew, 24 bytes

setstring(exe, 64, "PE"); // PE header signature is 'PE\0\0'

setword(exe, 68, 0x14C); // PE.Machine = IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386

setword(exe, 70, 0); // PE.NumberOfSections = 1

setword(exe, 84, 0); // PE.SizeOfOptionalHeader = offset between the optional header and the section table

setword(exe, 86, 0x103); // PE.Characteristics = IMAGE_FILE_32BIT_MACHINE | IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE | IMAGE_FILE_RELOCS_STRIPPED

// 3. OPTIONAL HEADER, follows PE header, 96 bytes

setword(exe, 88, 0x10B); // Optional header signature is 10B

setdword(exe, 104, 296); // Opt.AddressOfEntryPoint = RVA where code execution should begin

setdword(exe, 116, 0x400000); // Opt.ImageBase = base address at which to load the program, 0x400000 is standard

setdword(exe, 120, 2048); // Opt.SectionAlignment = alignment of section in memory at run-time, 4096 is standard

setdword(exe, 124, 512); // Opt.FileAlignment = alignment of sections in file, 512 is standard

setword(exe, 136, 4); // Opt.MajorSubsystemVersion = minimum OS version required to run this program

setdword(exe, 144, 4096*2); // Opt.SizeOfImage = total run-time memory size of all sections and headers

setdword(exe, 148, 0); // Opt.SizeOfHeaders = total file size of header info before the first section

setword(exe, 156, 3); // Opt.Subsystem = IMAGE_SUBSYSTEM_WINDOWS_CUI, command-line program

setdword(exe, 180, 14); // Opt.NumberOfRvaAndSizes = number of data directories following

// 4. DATA DIRECTORIES, follows optional header, 8 bytes per directory

// offset and size for each directory is zero

// 5. SECTION TABLE, follows data directories, 40 bytes

// no section table

// 6. .TEXT SECTION, at sectHdr.PointerToRawData (aligned to Opt.FileAlignment)

setbyte(exe, 296, 0x6A); // PUSH

setbyte(exe, 297, 0x2C); // value to push

setbyte(exe, 298, 0x58); // POP EAX

setbyte(exe, 299, 0xC3); // RETN

return 328; // size of exe

}

Here’s another pretty picture, showing the 328 byte executable file:

Maximum Shrinking

328 bytes was pretty good, but of course I wanted to do better. A popular technique seen in other “small PE” examples is to move down the PE header and everything that follows it, so that it overlaps the DOS header. This is possible because most of the DOS header is just wasted space, as far as a Windows executable is concerned.

The PE header can be moved down as low as offset 4 within the file. It must be 4-byte aligned, and it can’t be at offset 0 because then it would overwrite the required ‘MZ’ signature at the start of the file. Doing this is simple: just move everything but the DOS header down by 60 bytes.

The only complication with overlapping the DOS and PE headers this way is with the DWORD at file offset 60. This value is the e_lfanew parameter that gives the file offset to the PE header, so it now must be 4. But due to the overlapping, it’s also the Opt.SectionAlignment parameter that specifies the alignment between sections in memory at run-time. Hopefully Windows is OK with a 4-byte section alignment! It turns out that it’s fine, but only if Opt.FileAlignment is also 4. I’m not sure why.

These changes should have been enough to shrink the file to 240 bytes, but once again the OS seems to require 28 bytes of padding at the end of the file. Here’s the updated 268 byte version of BuildExe():

DWORD BuildExe(BYTE* exe)

{

// 1. DOS HEADER, 64 bytes

setstring(exe, 0, "MZ"); // DOS header signature is 'MZ'

// don't set DOS.e_lfanew, it's part of the overlapped PE header

// 2. PE HEADER, at offset DOS.e_lfanew, 24 bytes

setstring(exe, 64-60, "PE"); // PE header signature is 'PE\0\0'

setword(exe, 68-60, 0x14C); // PE.Machine = IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386

setword(exe, 70-60, 0); // PE.NumberOfSections = 1

setword(exe, 84-60, 0); // PE.SizeOfOptionalHeader = offset between the optional header and the section table

setword(exe, 86-60, 0x103); // PE.Characteristics = IMAGE_FILE_32BIT_MACHINE | IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE | IMAGE_FILE_RELOCS_STRIPPED

// 3. OPTIONAL HEADER, follows PE header, 96 bytes

setword(exe, 88-60, 0x10B); // Optional header signature is 10B

setdword(exe, 104-60, 296-60); // Opt.AddressOfEntryPoint = RVA where code execution should begin

setdword(exe, 116-60, 0x400000); // Opt.ImageBase = base address at which to load the program, 0x400000 is standard

setdword(exe, 120-60, 4); // Opt.SectionAlignment = alignment of section in memory at run-time, 4096 is standard

setdword(exe, 124-60, 4); // Opt.FileAlignment = alignment of sections in file, 512 is standard

setword(exe, 136-60, 4); // Opt.MajorSubsystemVersion = minimum OS version required to run this program

setdword(exe, 144-60, 4096*2); // Opt.SizeOfImage = total run-time memory size of all sections and headers

setdword(exe, 148-60, 0); // Opt.SizeOfHeaders = total file size of header info before the first section

setword(exe, 156-60, 3); // Opt.Subsystem = IMAGE_SUBSYSTEM_WINDOWS_CUI, command-line program

setdword(exe, 180-60, 14); // Opt.NumberOfRvaAndSizes = number of data directories following

// 4. DATA DIRECTORIES, follows optional header, 8 bytes per directory

// offset and size for each directory is zero

// 5. SECTION TABLE, follows data directories, 40 bytes

// no section table

// 6. .TEXT SECTION, at sectHdr.PointerToRawData (aligned to Opt.FileAlignment)

setbyte(exe, 296-60, 0x6A); // PUSH

setbyte(exe, 297-60, 0x2C); // value to push

setbyte(exe, 298-60, 0x58); // POP EAX

setbyte(exe, 299-60, 0xC3); // RETN

return 268; // size of exe

}

And another pretty picture, with some color blending going on where data structures overlap:

According to several sources, 268 bytes is the absolute minimum size for a working executable under Windows 7 64-bit edition. There are other tricks that would shrink the header even more, but then I’d just have to add more padding. I can go no further!

Read 15 comments and join the conversationAssembly Language Windows Programming

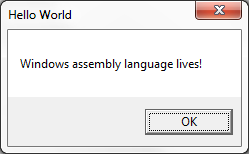

Who says assembly language programming is dead? Keeping with my recent theme of peering inside Windows executable files, I decided to bypass C++ completely and try writing a Windows program entirely in assembly language. I was happy to discover that it’s not difficult, especially if you have a bit of prior assembly experience for any CPU. My first example ASM program is only 17 lines! Granted it doesn’t do very much, but it demonstrates a skeleton that can be extended to create exactly the program I want – no more futzing around with C compiler options to prevent mystery “features” from being added to my code. Yes, I am a control freak.

1. Minimal Assembly Example

Here’s a simple example:

.686 .model flat, stdcall EXTERN MessageBoxA@16 : proc EXTERN ExitProcess@4 : proc .const msgText db 'Windows assembly language lives!', 0 msgCaption db 'Hello World', 0 .code Main: push 0 push offset msgCaption push offset msgText push 0 call MessageBoxA@16 push eax call ExitProcess@4 End Main

If you’ve got any version of Microsoft Visual Studio installed on your PC, including the free Visual Studio Express versions, then you’ve already got MASM: the Microsoft Macro Assembler. Save the example file as msgbox.asm, and use MASM to build it from the command line like this:

> ml /coff /c /Cp msgbox.asm > link /subsystem:windows /out:msgbox.exe kernel32.lib user32.lib msgbox.obj

That doesn’t look too complicated. Let’s examine it line by line.

.686

This tells the assembler to generate x86 code that’s compatible with the Intel 686 CPU or later, aka the Pentium Pro. Any Intel-based machine from the past 15-20 years will be able to run this, so it’s a good generic default. You can also use .386, .486, or .586 here if you want to avoid generating any instructions not compatible with those older CPUs.

.model flat, stdcall

The memory model for all Win32 programs is always flat. The second parameter gives the default calling convention for procedures exported from this file, and can be either C or stdcall. Nothing is exported in this example, so the choice doesn’t really matter, but I’ll choose stdcall.

When one function calls another, it must somehow pass the arguments to the called function. The caller and callee must agree on where the arguments will be placed, and in what order, or else the code won’t work correctly. If the arguments are passed on the stack, then the two functions must also agree on who’s responsible for popping them off afterwards, so the stack can be restored to its original state. These details are known as the calling convention.

All of the Win32 API functions use the __stdcall convention, while C functions and the C library use the __cdecl (or just plain “C”) convention. You may also rarely see the __fastcall convention; look it up for more details. stdcall and cdecl conventions are similar: both pass arguments on the stack, and the arguments are pushed in right to left order. So a function whose prototype looks like:

MyFuction(arg1, arg2, arg3)

is called by pushing arg3 onto the stack first, followed by arg2 and arg1:

push arg3 push arg2 push arg1 call MyFunction

These two conventions only differ regarding stack cleanup. With cdecl, the calling function is responsible for removing arguments from the stack, whereas with stdcall it’s the called function’s responsibility to do stack cleanup before it returns.

EXTERN MessageBoxA@16 : proc

EXTERN ExitProcess@4 : proc

These lines tell MASM that the code makes reference to two externally-defined procedures. When the code is assembled into an .obj file, references to these procedures will be left pending. When the .obj file is later linked to create the finished executable, it must be linked with other .obj files or libraries that provide the definitions for these external references. If definitions aren’t found, you’ll see the familiar linker error message complaining of an “unresolved external symbol”.

The funny @4 and @16 at the end of the function names is the standard method of name mangling for stdcall functions, including all Win32 functions. A suffix is added to the name of the function, with the @ symbol and the total number of bytes of arguments expected by the function. This mangled name is the symbol that appears in the .obj file or library, and not the original name. The actual symbol name is also prefixed with an underscore, e.g. _MessageBox@16, but MASM handles this automatically by prefixing an underscore to all statically imported or exported public symbols.

To find the number of bytes of arguments expected by a Win32 stdcall function, you can view the online MSDN reference and add up the argument sizes manually, or you can use something like dumpbin /symbols user32.lib to view the mangled names of functions in an import library.

For cdecl functions, there’s no name mangling. The name of the symbol is just the name of the function prefixed with an underscore, e.g. _strlen.

Most of the time you don’t see this level of detail, because the compiler or assembler knows the calling convention and argument list of any functions you call, so it can do name mangling automatically behind the scenes. But in this example, I never told MASM what the calling convention is for MessageBox or ExitProcess, nor the number and sizes of the arguments they expect, so it can’t help with name mangling and I have to provide the mangled names manually. In a minute, I’ll show a nicer way to handle this with MASM.

.const

The .const directive indicates that whatever follows is constant read-only data, and should be placed in a separate section of the executable called .rdata. The memory for this section will have the read-only attribute enforced by the Windows virtual memory manager, so buggy code can’t modify it by mistake. Other possible data-related section directives are .data for read-write data, and .data? for uninitialized read-write data.

msgText db ‘Windows assembly language lives!’, 0

msgCaption db ‘Hello World’, 0

The next lines allocate and initialize storage for two pieces of data named msgText and msgCaption. Because the previous line was the .const directive, this data will be placed in the executable’s .rdata section. db is the assembler directive for “define byte”, and is followed by a list of comma separated byte values. The values can be numeric constants, string literals, or a mix of both as shown here. The 0 after each string literal is the null terminator byte for C-style strings.

.code

.code indicates the start of a new section, and whatever follows is program code rather than data. It will be placed in a section of the executable called .text. Why doesn’t the directive match the section name?

Main:

Here the code defines a label called Main, which can then be used as a target for jump instructions or other instructions that reference memory. Main refers to the address at which the next line of code is assembled. There’s nothing magic about the word “Main” here, and label names can be anything you want as long as they’re not MASM keywords.

push 0

push offset msgCaption

push offset msgText

push 0

This code pushes the arguments for MessageBox onto the stack, in right to left order as required by the stdcall convention. According to MSDN, the prototype of MessageBox is:

int WINAPI MessageBox(HWND hWnd, LPCTSTR lpText, LPCTSTR lpCaption, UINT uType);

The first argument pushed onto the stack is the value for uType, a 4-byte unsigned integer. The value 0 here corresponds to the constant MB_OK, and means the MessageBox should contain a single push button labeled “OK”. Next the addresses of the caption and text string constants are pushed. The offset keyword tells MASM to push the memory address of the strings, and not the strings themselves, and is similar to the & operator in C. Finally the hWnd argument is pushed, which is a handle to the owner of the message box. The value 0 used here means the message box has no owner.

call MessageBoxA@16

Now the Win32 MessageBox function is finally called. call will push the return address onto the stack, and then jump to the address of _MessageBoxA@16. It will use the arguments previously pushed onto the stack, display a message box, and wait for the user to click the OK button before returning. Because it’s a stdcall function, MessageBox will also remove the arguments from the stack before returning to the caller. The return value from calling MessageBox will be placed in the EAX register, which is the standard convention for Win32 functions.

Notice that the code specifically called MessageBoxA, with an A suffix that indicates the caption and text are single-byte ASCII strings. The alternative is MessageBoxW, which expects wide or double-byte Unicode strings. Many Win32 functions exist with both -A and -W variants like this.

push eax

call ExitProcess@4

The return value from MessageBox is pushed onto the stack, and ExitProcess is called. Its prototype looks like:

VOID ExitProcess(UINT uExitCode);

It takes a single argument for the program’s exit code. In this example, whatever value is returned by MessageBox will be used as the exit code. This is the end of the program – the call to ExitProcess never returns, because the program is terminated.

End Main

The end statement closes the last segment and marks the end of the source code. It must be at the end of every file. The optional address following end specifies the program’s entry point, where execution will begin after the program is loaded into memory. Alternatively, the entry point can be specified on the command line during the link step, using the /entry option.

ml /coff /c /Cp msgbox.asm

link /subsystem:windows /out:msgbox.exe kernel32.lib user32.lib msgbox.obj

ml is the name of the MASM assembler. Running it will create the msgbox.obj file.

/coff instructs MASM to create an object file in COFF format, compatible with recent Microsoft C compilers, so you can combine assembly and C objects into a single program.

/c tells MASM to perform only the assembly step, stopping after creation of the .obj file, rather than also attempting to do linking.

/Cp tells MASM to preserve the capitalization case of all identifiers.

link is the Microsoft linker, the same one that’s invoked behind the scenes when building C or C++ programs from Visual Studio.

/subsystem:windows means this is a Windows GUI-based program. Change this to /subsystem:console for a text-based program running in a console window.

/out:msgbox.exe is the name to give the executable file that will be generated.

The remainder of the line specifies the libraries and object files to be linked. MessageBox is implemented in user32 and ExitProcess in kernel32, so I’ve included those libraries. I didn’t provide the path to the libraries, so the linker will search the directories specified in the LIBPATH environment variable. The Visual Studio installer normally creates a shortcut in the start menu to help with this: it’s called “Developer Command Prompt for Visual Studio”, and it opens a console window with the LIBPATH and PATH environment variables set appropriately for wherever the development tools are installed.

2. Improvements with MASM Macros and MASM32

MASM is a “macro assembler”, and contains many macros that can make assembly programming much more convenient. For starters, I could define some constants to replace the magic zeroes in the arguments to MessageBox:

MB_OK equ 0h MB_OKCANCEL equ 1h MB_ABORTRETRYIGNORE equ 2h MB_YESNOCANCEL equ 3h MB_YESNO equ 4h MB_RETRYCANCEL equ 5h NULL equ 0

In the preceding example, I had to do manual name mangling of Win32 function names, and push the arguments onto the stack one at a time. This can be avoided by using the MASM directives PROTO and INVOKE. Much like a function prototype in C, PROTO tells MASM what calling convention a function uses, and the number and types of the arguments it expects. The function can then be called in a single line using INVOKE, which will verify that the arguments are correct, perform any necessary name mangling, and generate push instructions to place the arguments on the stack in the proper order. Using these directives, the lines related to MessageBoxA in the example program could be condensed like this:

MessageBoxA proto stdcall :DWORD,:DWORD,:DWORD,:DWORD

invoke MessageBoxA, NULL, offset msgText, offset msgCaption, MB_OK

Many people using MASM will use it in combination with MASM32, which provides a convenient set of include files containing prototypes for common Windows functions and constants. This enables the relevant lines of the MessageBox example to be further simplified to:

include \masm32\include\windows.inc

include \masm32\include\user32.inc

invoke MessageBoxA, NULL, offset msgText, offset msgCaption, MB_OK

Take a look at Iczelion’s excellent tutorial for a MessageBox example program making good use of all the MASM and MASM32 convenience features.

3. Structured Programming with MASM

The biggest headache writing any kind of non-trivial assembly language program is that all the little details quickly become tedious. A simple if/else construct must be written as a CMP instruction combined with a few conditional and unconditional jumps around the separate clauses. Allocating and using local variables on the stack is a pain. Working with objects and structures requires calculating the offset of each field from the base of the structure. It’s a giant hassle.

Nothing can relieve all the tedium (this is assembly language after all), but MASM is a big help. Directives like .IF, .ELSE, and .LOCAL make it possible to write assembly code that almost looks like C. Instructions are automatically generated to reserve and free space for stack-based locals, and the locals can be referenced by name instead of with awkward constructs like EBP-8. MASM also supports the declaration of C-style structs with named and typed fields. The result can be assembly code that’s surprisingly readable. Borrowing snippets from another Iczelion tutorial:

; structure definition from windows.inc

WNDCLASSEXA STRUCT

cbSize DWORD ?

style DWORD ?

lpfnWndProc DWORD ?

cbClsExtra DWORD ?

; ... more fields

WNDCLASSEXA ENDS

WinMain proc hInst:HINSTANCE, hPrevInst:HINSTANCE, CmdLine:LPSTR, CmdShow:DWORD

LOCAL wc:WNDCLASSEX

LOCAL msg:MSG

mov wc.cbSize, SIZEOF WNDCLASSEX

mov wc.style, CS_HREDRAW or CS_VREDRAW

mov wc.lpfnWndProc, OFFSET WndProc

mov wc.cbClsExtra, NULL

; ... more code

invoke RegisterClassEx, addr wc

; ... more code

.WHILE TRUE

invoke GetMessage, ADDR msg, NULL, 0, 0

.BREAK .IF (!eax)

invoke TranslateMessage, ADDR msg

invoke DispatchMessage, ADDR msg

.ENDW

mov eax, msg.wParam

ret

WinMain endp

This almost reads like C, and you might wonder how different it really is from writing C code. Despite the appearance, it’s still 100 percent assembly language, and the instructions in the .asm file are exactly what will appear in the final executable. There’s no optimization happening, no instruction reordering, and no true code generation in any complex sense. Directives like LOCAL that hide individual assembly instructions are just complex macros.

If I find enough motivation, I’ll write another post soon that shows a more full-featured assembly language program using these techniques. Now if you want to know WHY in the 21st century someone would write Windows programs in assembly language, I don’t have a great answer. It might be useful if you need to do something extremely specific or performance critical. But if you’re like me, the only reason needed is that fact that it’s there, underlying everything that’s normally done with higher level languages. Whenever I see a black box like that, I want to open the lid and peek inside.

Read 7 comments and join the conversationWhat Happens Before main()

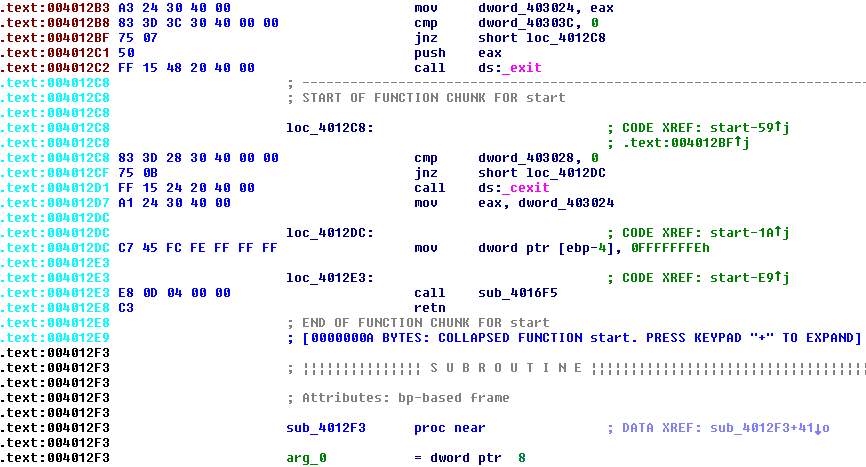

Did you know that a C program’s main() function is not the first code to be run? Depending on the program and the compiler, there are all kinds of interesting and complex functions that get run before main(), automatically inserted by the compiler and invisible to casual observers. For the past several days I’ve been on a quest to reverse engineer a minimal C program, to see what’s inside the executable file and how it’s put together. I was generally aware that some kind of special initialization happened before main() was called, but knew nothing about the details. As it turned out, understanding what happens before main() proved to be central to explaining large chunks of mystery code that I’d struggled with during my first analysis.

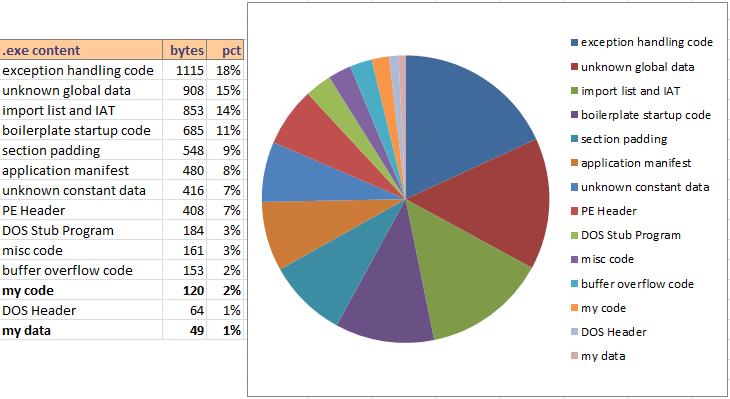

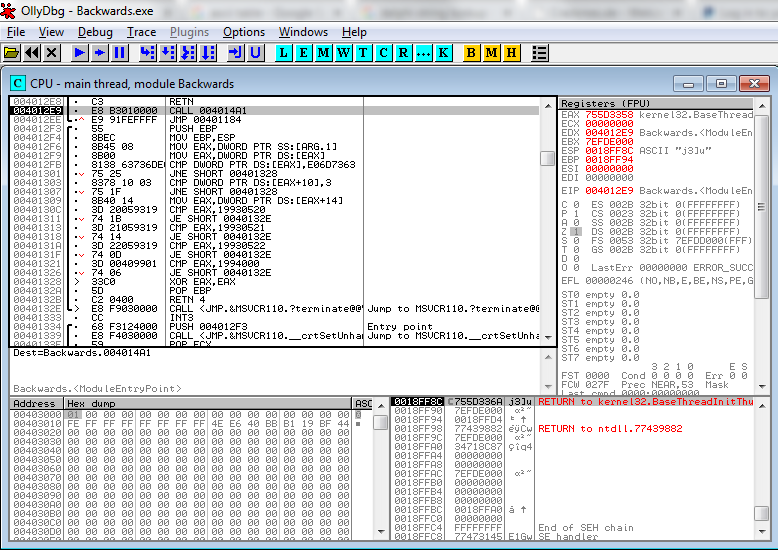

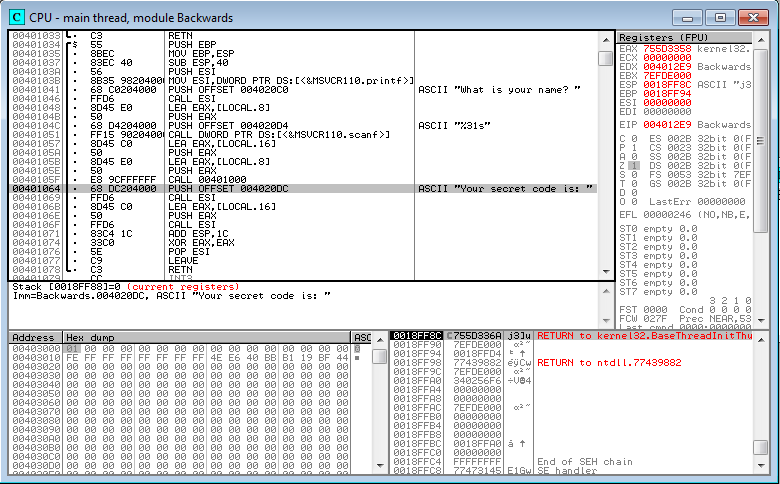

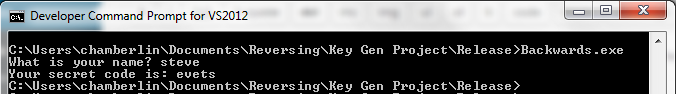

In my previous post, I used dumpbin, OllyDbg, and the IDA disassembler to examine the contents of a Windows executable file created from an 18 line C program. This example program is a text console application that only references printf, scanf, and strlen. The C functions compile into 120 bytes of x86 code. Yet dumpbin revealed that the executable file contained 2234 bytes of code, and imported 38 different functions from DLLs. It also located over 1300 bytes of unknown data and constants. The implementations of printf etc were in a C runtime library DLL, so that couldn’t explain the unexpected code bloat. Something else was at work.

Scaffold for a C Program

By compiling with debug symbols, loading the executable in a debugger, and examining the disassembly, I was able to see the true structure of the example program. This included all the things happening behind the scenes. You can view the complete disassembly with symbols here. Here’s an outline, based on compiling with Microsoft Visual Studio Express 2012, for a release build with compiler settings selected to eliminate all extras like C++ exception handling and array bounds checking. Pseudocode function names are my descriptions and don’t necessarily match the names obtained from debug symbols.

ProgramEntryPoint()

{

security_init_cookie();

// beginning of __tmainCRTStartup()

setup_SEH_frame();

// call init functions from a table of function pointers:

// from pre_c_init()

is_managed_app = ParseAppHeader(); // checks for initial "MZ" bytes, PE header fields

init_exit_callbacks();

run_time_error_checking_initialize(); // calls init functions from an empty table

matherr();

setusermatherr(matherr);

setdefaultprecision(); // calls controlfp_s(0) and maybe calls invoke_watson()

configthreadlocale(); // for C library function string formatting of numbers and time

CxxSetUnhandledExceptionFilter(myExceptionFilter);

// from pre_cpp_init()

register_exit_callback(run_time_error_checking_terminate);

get_command_line_args();

// check tls_init_callback

if (dynamic_thread_local_storage_callback != 0 && IsNonWritableInCurrentImage())

{

dynamic_thread_local_storage_callback();

}

// now the C program runs

retVal = main();

// C program has now finished

if (!is_managed_app)

{

// clean-up C library, and terminate process

exit(retVal);

}

else

{

// clean-up C library, but do not terminate process

cexit();

cleanup_SEH_frame();

return retVal;

}

}

IsNonWritableInCurrentImage()

{

check_security_cookie();

return (ValidateImageBase() &&

IsNonWritable(FindPESection()));

}

myExceptionFilter()

{

if (IsRecognizedExceptionType())

{

terminate();

break_in_debugger();

}

}

register_exit_callback(pCallback)

{

setup_SEH_frame();

onexit(pCallback);

// also maintains onexit callbacks for DLLs

cleanup_SEH_frame();

}

This was enough to help me identify the general purpose of most of the code in the executable file, even if the details weren’t all entirely clear. During the program analysis in my previous post, I was confused by large chunks of code that didn’t appear to be called from anywhere. The answer to that mystery was tables of function pointers, which I discovered are used in many places during program startup to call a whole series of initialization functions. The addresses of the functions are stored in a table in the data section, and then the address of the table is passed to _initterm. I’d thought _initterm had something to do with terminal settings, but it’s actually just a helper function to iterate over a table and call each function.

Even with that mystery explained, there were still quite a few snippets of unreachable code in the disassembly. Most of these were only 5 or 10 lines of code, and appeared to be related to other nearby functions. My guess is that many of these scaffold/startup functions were written in assembly language by Microsoft developers, and the linker can’t tell which lines are actually used or not. As a result of some conditionally-included features, or just carelessness on the part of the compiler development team, a few lines of orphaned code were left over and got included into my example program’s executable.

Exploring the Scaffold Functions

Let’s start at the entry point and work our way through the scaffold functions.

security_init_cookie is related to a compiler-generated security feature that checks for buffer overruns. This function generates a cookie value based on the current time and other data that’s difficult for an attacker to predict. On entry to an overrun-protected function, the cookie is put on the stack, and on exit, the value on the stack is compared with the global cookie. In this example program, buffer overrun checking was explicitly disabled in the compiler settings, yet security_init_cookie is called anyway. Hmm.

Next the structured exception handling frame is configured on the stack. SEH is a Windows mechanism that’s used to catch and handle CPU exceptions. I’ve never used them, but I believe they can be used to handle errors like division by zero or invalid memory references.

The next set of functions are called from a pointer table that’s placed in the data section, rather than by direct function calls. The code parses the in-memory executable header, including the DOS and PE headers, to determine whether this is a managed app or if it’s native code. It then initializes the exit callbacks, a mechanism that can be used to register other functions to be called when the program exits. Following this, it calls a function to initialize run-time error checks, another compiler-generated feature that can catch problems with type conversions and uninitialized variables. In the example program, run-time error checks were disabled in the compiler settings. The call to init RTC is still present, but it uses an empty table of function pointers to do its work, and so it ultimately does nothing.

After this it calls the math error handler, and then installs that error handler. I’m not sure why it directly calls the math error handler first, but it’s a stub function that does nothing and returns zero.

The call after the math handler initialization is to an internal function called setdefaultprecision, which sets the precision used for floating point calculations. The implementation of this function is curious. It calls controlfp_s(0) to set the precision, and if this returns an error, it invokes the Doctor Watson debugger. This is the only place in any of the scaffolding code where Doctor Watson is referenced or used. If it’s used at all, I would have expected to see it as part of the exception handling mechanism, but in fact it’s only called here during initialization of the floating point precision.

The last task performed by pre_c_init is to configure the locale settings, to help make correctly-formatted numbers and date strings in the C standard library functions.

Next, the scaffold code registers a handler to be used for SEH exceptions. This handler is mostly useless. If the exception is one of four recognized types, the handler calls terminate and then performs an INT 3 debugger break. Otherwise it just returns without doing anything.

After that, the code registers an exit callback function which terminates the run-time error checking feature. The registration mechanism makes use of SEH frames. It also appears to handle exit functions for DLLs, although I was unclear about exactly how that works. I assume that if a DLL used by the program needs to perform some kind of clean-up code or destructors before the program exits, it can register a callback here.

get_command_line_args does what it sounds like, and initializes argc, argv, and envp. I never really thought about it before, but of course these need to be provided by the operating system somehow, and this is where it happens.

The next piece of code is the most complicated and confusing of the whole lot. The code checks the value of something called __dyn_tls_init_callback, which is a global variable initialized to zero in the program’s .data section. This appears related to thread local storage – an area of memory that’s unique for each thread. If __dyn_tls_init_callback is not zero (though I don’t see any mechanism that could make it be non-zero), it calls another internal function called IsNonWritableInCurrentImage. This is the beginning of a fairly involved group of functions that scan the in-memory DOS and PE headers, and attempt to locate a particular section in the PE header. Depending on what it finds there, it may or may not call the __dyn_tls_init_callback function. Notably, IsNonWritableInCurrentImage also makes use of the security cookie for detecting buffer overruns.

Finally, after all this setup work, at last it’s time to call the C main() function. Hooray! This is where the real work happens, and what most people think of as “the program” when they talk about a C-based software application.

Eventually the C program finishes its work, and control returns from main(). The scaffolding code is now responsible for cleaning things up and shutting everything down in an orderly manner. If it was previously determined that this is not a managed app, the code simply calls exit() to terminate the process. On the other hand, if it is a managed app, the scaffold code calls cexit(), cleans up the SEH frame, and returns control to whomever originally called the entry point.

Efficiency

From my description, I hope it’s clear that the scaffold functions aren’t especially space-efficient. Probably most people don’t care about a few hundred or few thousand bytes of code wasted, but it’s easy to see where some optimizations could be made:

When the compiler knows ahead of time that RTC checking is disabled, it should completely eliminate the functions related to RTC initialization and cleanup, instead of retaining them but having them iterate over an empty function table.

If the main() function doesn’t use argc and argv, then don’t bother to call get_command_line_args().

The compiler must know whether it’s making a native or managed app, so it can set the scaffold behavior as needed for each case. This would be far simpler than including code to parse the PE header at runtime, and shutdown/cleanup code that must handle both native and managed cases.

Bypassing the Scaffolding

While the inefficiencies of the scaffold code are annoying, what’s more bothersome is that many of the scaffold features simply can’t be turned off by any compiler setting that I’ve found. If we group the scaffold functions into broad categories, it looks like this:

- buffer overrun detection

- SEH handling

- run-time error checks (RTC)

- math error handling and default precision

- exit callbacks

- thread local storage

- command line args

- managed/native app detection

- locale settings

It would be great if there were compiler settings that could be used to disable each of these features when appropriate, for squeezing the last few hundred bytes out of the code. What’s maddening is that there are settings to disable the first two, but it appears they only prevent the features from being used in the main body of code. Support for the features is still present in the executable, because the scaffolding code uses them.

Another approach is to define a custom entry point for the program, and bypass the scaffolding completely. This could be as simple as adding

int MyEntryPoint()

{

return main(0, NULL);

}

and then setting the program’s entry point to MyEntryPoint in the advanced linker settings. This causes all of the standard scaffold code to be omitted, and with my example program it shrunk the executable from 6144 to 2560 bytes. It also drastically reduced the number of external functions in the imports list, from 38 to 3.

Caution: when using this approach, none of the standard systems will be initialized. The program will misbehave or crash if it attempts to use the command line args, or thread local storage, or locale-dependent functions in the C runtime. The custom entry point can initialize many of these manually if needed. Most of the necessary functions like __getmainargs are documented in MSDN. The rest can be handled by using the debugger to examine the scaffold code, and copying what it does.

Read 7 comments and join the conversationDissecting Bloated Executables

Did you ever wonder what’s used to stuff the sausage of a Windows executable file? In yesterday’s post I examined a simple text-only C program, and discovered that 18 lines of C code created a 6144 byte executable program. Using OllyDbg, I learned that the functions I wrote compiled into only 120 bytes of code, but the executable was 50 times larger than that. This was true even when the C runtime library was in a DLL instead of statically linked, code was compiled in release mode and optimization was set for “minimum size”, and all the advanced compiler and linker options were turned off in an effort to eliminate surprises. No hot-patching support, C++ exception handling, function inlining, buffer overrun checks, security development lifecycle checks, whole program optimization, etc. The complete set of command line switches for the compiler and linker were as follows (using Microsoft Visual Studio Express 2012):

/Yu"stdafx.h" /GS- /analyze- /W3 /Gy- /Zc:wchar_t /Zi /Gm- /O1 /Ob0 /sdl- /Fd"Release\vc110.pdb" /fp:precise /D "WIN32" /D "NDEBUG" /D "_CONSOLE" /D "_CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS" /D "_MBCS" /errorReport:none /WX- /Zc:forScope /Gd /Oy- /MD /Fa"Release\" /nologo /Fo"Release\" /Fp"Release\Backwards.pch" /OUT:"C:\Users\chamberlin\Documents\Reversing\Release\Backwards.exe" /MANIFEST /NXCOMPAT /PDB:"C:\Users\chamberlin\Documents\Reversing\Release\Backwards.pdb" /DYNAMICBASE:NO "kernel32.lib" "user32.lib" "gdi32.lib" "winspool.lib" "comdlg32.lib" "advapi32.lib" "shell32.lib" "ole32.lib" "oleaut32.lib" "uuid.lib" "odbc32.lib" "odbccp32.lib" /MACHINE:X86 /OPT:REF /SAFESEH:NO /INCREMENTAL:NO /PGD:"C:\Users\chamberlin\Documents\Reversing\Release\Backwards.pgd" /SUBSYSTEM:CONSOLE /MANIFESTUAC:"level='asInvoker' uiAccess='false'" /ManifestFile:"Release\Backwards.exe.intermediate.manifest" /OPT:ICF /ERRORREPORT:NONE /NOLOGO /TLBID:1

The Windows PE Header

What else is eating up all that space in the executable file? For starters, every Windows executable begins with a header that describes its contents. In fact, there are two headers. The first 256 bytes of any modern Windows application is actually a legacy DOS executable header and a small 16-bit DOS program. The DOS header begins with the two letters MZ (ASCII 4D 5A), which you can see by opening the executable file in any binary editor. The DOS program is a hold-over from the early days of Windows, when a confused person might try to run a Windows program from inside DOS. Copy a modern Windows executable file to an ancient DOS box and run it, and the embedded DOS program will print a message like “This program cannot be run in DOS mode.” Score 1 for backwards compatibility.

Following the DOS header and stub program is a Windows PE (portable executable) header, where all the interesting stuff is found. The PE header has a variable size, but is typically a few hundred bytes, and is 408 bytes for the example program described here. The PE header is used by the Windows loader to place the program’s code and data into memory, and to perform run-time dynamic linking with DLLs. It describes what sections the executable has, what functions it imports, and lots of other goodies. The PE header can be explored using the Microsoft tool dumpbin, which is included with a standard install of Visual Studio. Running dumpbin /headers on the example program produces this output:

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 11.00.50727.1

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Dump of file Backwards.exe

PE signature found

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

FILE HEADER VALUES

14C machine (x86)

4 number of sections

560B1034 time date stamp Tue Sep 29 15:27:00 2015

0 file pointer to symbol table

0 number of symbols

E0 size of optional header

103 characteristics

Relocations stripped

Executable

32 bit word machine

OPTIONAL HEADER VALUES

10B magic # (PE32)

11.00 linker version

A00 size of code

C00 size of initialized data

0 size of uninitialized data

12E9 entry point (004012E9)

1000 base of code

2000 base of data

400000 image base (00400000 to 00404FFF)

1000 section alignment

200 file alignment

6.00 operating system version

0.00 image version

6.00 subsystem version

0 Win32 version

5000 size of image

400 size of headers

0 checksum

3 subsystem (Windows CUI)

8100 DLL characteristics

NX compatible

Terminal Server Aware

100000 size of stack reserve

1000 size of stack commit

100000 size of heap reserve

1000 size of heap commit

0 loader flags

10 number of directories

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Export Directory

21B4 [ 3C] RVA [size] of Import Directory

4000 [ 1E0] RVA [size] of Resource Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Exception Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Certificates Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Base Relocation Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Debug Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Architecture Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Global Pointer Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Thread Storage Directory

2100 [ 40] RVA [size] of Load Configuration Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Bound Import Directory

2000 [ A0] RVA [size] of Import Address Table Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Delay Import Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of COM Descriptor Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Reserved Directory

SECTION HEADER #1

.text name

8BA virtual size

1000 virtual address (00401000 to 004018B9)

A00 size of raw data

400 file pointer to raw data (00000400 to 00000DFF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

60000020 flags

Code

Execute Read

SECTION HEADER #2

.rdata name

526 virtual size

2000 virtual address (00402000 to 00402525)

600 size of raw data

E00 file pointer to raw data (00000E00 to 000013FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

40000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Only

SECTION HEADER #3

.data name

38C virtual size

3000 virtual address (00403000 to 0040338B)

200 size of raw data

1400 file pointer to raw data (00001400 to 000015FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

C0000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Write

SECTION HEADER #4

.rsrc name

1E0 virtual size

4000 virtual address (00404000 to 004041DF)

200 size of raw data

1600 file pointer to raw data (00001600 to 000017FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

40000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Only

Summary

1000 .data

1000 .rdata

1000 .rsrc

1000 .text

This executable has four sections:

- .text (8BA hex or 2234 decimal bytes)

- .rdata (526 hex or 1318 decimal bytes)

- .data (38C hex or 908 decimal bytes)

- .rsrc (1E0 hex or 480 decimal bytes)

That’s 4940 total bytes of raw section data, but each section must be 512 byte aligned. Including the alignment padding, the four sections combined use 5488 bytes on disk. So that’s where the bulk of the file’s data lies.

Imports

The PE header also contains the executable’s imports: the list of DLLs that it requires and the functions that are used in each DLL. For this text-only console-based example program, I would expect to see a couple of functions like printf and scanf imported from the C runtime library, and maybe a few other functions imported from kernel32.dll for creating and managing the console window. I can use dumpbin /imports to to parse the PE header and display the imports list:

Dump of file Backwards.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

Section contains the following imports:

MSVCR110.dll

402024 Import Address Table

402214 Import Name Table

0 time date stamp

0 Index of first forwarder reference

21C _cexit

22C _configthreadlocale

1E2 __setusermatherr

2EF _initterm_e

2EE _initterm

1A5 __initenv

284 _fmode

22B _commode

13B ?terminate@@YAXXZ

269 _exit

36C _lock

4D6 _unlock

21B _calloc_crt

19C __dllonexit

412 _onexit

2F6 _invoke_watson

22F _controlfp_s

260 _except_handler4_common

23B _crt_debugger_hook

19A __crtUnhandledException

199 __crtTerminateProcess

5BC exit

1E0 __set_app_type

1A4 __getmainargs

205 _amsg_exit

16F _XcptFilter

649 strlen

630 scanf

198 __crtSetUnhandledExceptionFilter

620 printf

KERNEL32.dll

402000 Import Address Table

4021F0 Import Name Table

0 time date stamp

0 Index of first forwarder reference

383 IsDebuggerPresent

117 DecodePointer

311 GetTickCount64

2F4 GetSystemTimeAsFileTime

228 GetCurrentThreadId

43C QueryPerformanceCounter

13C EncodePointer

388 IsProcessorFeaturePresent

Wow! There are a lot more functions imported from the C runtime library than you might have expected, including some odd-looking ones like _invoke_watson and _crt_debugger_hook, and several functions related to exception handling. Remember, C++ exception handling was disabled in the compiler options, so seeing these functions imported here is something of a surprise. But the really strange discovery is the list of functions imported from kernel32.dll. Why does it need to check if a debugger is present, or use functions like GetTickCount64 or QueryPerformanceCounter? There’s nothing timing-related at all in the example program, so the presence of these imports is a complete mystery. Hopefully I can find an explanation later when I examine the other parts of the executable.

Exploring the Sections

.reloc

The executable originally had a 960 byte .reloc section too, but I suppressed that. Code in the .text segment is assembled using absolute addressing, assuming it will be loaded at a fixed image base (typically 00400000). If the Windows loader can’t place the program at that address, it will choose a different base address, and use the information in the .reloc segment to find absolute address references in the code that need to be patched.

But I think this feature is no longer needed today, thanks to virtual memory. Each program gets its own private virtual address space, so what could possibly conflict with it such that it couldn’t be loaded at 00400000? Indeed, none of the other example programs I looked at had a .reloc section, but mine did. It turned out that Visual Studio was adding a .reloc section by default, as a result of the Randomize Base Address feature controlled by the /DYNAMICBASE command line switch. This feature chooses a different base address at which to load the program every time it’s run, which I guess is some kind of security feature. After specifying /DYNAMICBASE:NO for the linker, the .reloc section disappeared and the program continued to run fine.

.rsrc

What about that resource section, .rsrc? It’s normally used to hold Windows resources like cursors and images, but this is a text-only console program. It doesn’t need any resources, so why is the .rsrc section there at all? I can use dumpbin again to look at the raw data in the .rsrc section, with dumpbin /section:.rsrc /rawdata:

SECTION HEADER #4

.rsrc name

1E0 virtual size

4000 virtual address (00404000 to 004041DF)

200 size of raw data

1600 file pointer to raw data (00001600 to 000017FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

40000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Only

RAW DATA #4

00404000: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 ................

00404010: 18 00 00 00 18 00 00 80 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00404020: 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 01 00 00 00 30 00 00 80 ............0...

00404030: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 ................

00404040: 09 04 00 00 48 00 00 00 60 40 00 00 7D 01 00 00 ....H...`@..}...

00404050: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00404060: 3C 3F 78 6D 6C 20 76 65 72 73 69 6F 6E 3D 27 31 <?xml version='1

00404070: 2E 30 27 20 65 6E 63 6F 64 69 6E 67 3D 27 55 54 .0' encoding='UT

00404080: 46 2D 38 27 20 73 74 61 6E 64 61 6C 6F 6E 65 3D F-8' standalone=

00404090: 27 79 65 73 27 3F 3E 0D 0A 3C 61 73 73 65 6D 62 'yes'?>..<assemb

004040A0: 6C 79 20 78 6D 6C 6E 73 3D 27 75 72 6E 3A 73 63 ly xmlns='urn:sc

004040B0: 68 65 6D 61 73 2D 6D 69 63 72 6F 73 6F 66 74 2D hemas-microsoft-

004040C0: 63 6F 6D 3A 61 73 6D 2E 76 31 27 20 6D 61 6E 69 com:asm.v1' mani

004040D0: 66 65 73 74 56 65 72 73 69 6F 6E 3D 27 31 2E 30 festVersion='1.0

004040E0: 27 3E 0D 0A 20 20 3C 74 72 75 73 74 49 6E 66 6F '>.. <trustInfo

004040F0: 20 78 6D 6C 6E 73 3D 22 75 72 6E 3A 73 63 68 65 xmlns="urn:sche

00404100: 6D 61 73 2D 6D 69 63 72 6F 73 6F 66 74 2D 63 6F mas-microsoft-co

00404110: 6D 3A 61 73 6D 2E 76 33 22 3E 0D 0A 20 20 20 20 m:asm.v3">..

00404120: 3C 73 65 63 75 72 69 74 79 3E 0D 0A 20 20 20 20 <security>..

00404130: 20 20 3C 72 65 71 75 65 73 74 65 64 50 72 69 76 <requestedPriv

00404140: 69 6C 65 67 65 73 3E 0D 0A 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 ileges>..

00404150: 20 3C 72 65 71 75 65 73 74 65 64 45 78 65 63 75 <requestedExecu

00404160: 74 69 6F 6E 4C 65 76 65 6C 20 6C 65 76 65 6C 3D tionLevel level=

00404170: 27 61 73 49 6E 76 6F 6B 65 72 27 20 75 69 41 63 'asInvoker' uiAc

00404180: 63 65 73 73 3D 27 66 61 6C 73 65 27 20 2F 3E 0D cess='false' />.

00404190: 0A 20 20 20 20 20 20 3C 2F 72 65 71 75 65 73 74 . </request

004041A0: 65 64 50 72 69 76 69 6C 65 67 65 73 3E 0D 0A 20 edPrivileges>..

004041B0: 20 20 20 3C 2F 73 65 63 75 72 69 74 79 3E 0D 0A </security>..

004041C0: 20 20 3C 2F 74 72 75 73 74 49 6E 66 6F 3E 0D 0A </trustInfo>..

004041D0: 3C 2F 61 73 73 65 6D 62 6C 79 3E 0D 0A 00 00 00 </assembly>.....

Interesting… there’s a plain-text XML file in the resource section. This is the Windows application manifest, and is used to indicate whether the program needs administrator privileges in order to run, kind of like the setuid flag under Linux. I believe the manifest can also be used to select a specific DLL to use with the program, if multiple versions of the same DLL exist. Does this program actually need a manifest? I’m not sure, but with padding it’s taking up 512 bytes.

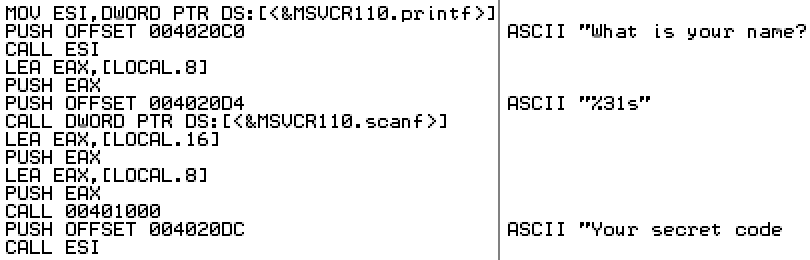

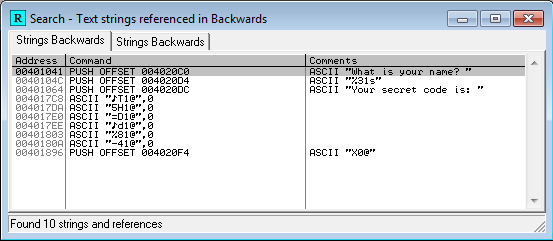

.rdata

Next let’s look at the read-only data section, .rdata. The example program contains three string constants that would seem to be the only candidates for read-only data, and they’re maybe 50 total bytes. What else is in the .rdata section to make it 1318 bytes? I can use dumpbin again to peek inside:

SECTION HEADER #2

.rdata name

526 virtual size

2000 virtual address (00402000 to 00402525)

600 size of raw data

E00 file pointer to raw data (00000E00 to 000013FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

40000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Only

RAW DATA #2

00402000: E8 24 00 00 D8 24 00 00 C6 24 00 00 AC 24 00 00 è$..O$..Æ$..¬$..

00402010: 96 24 00 00 7C 24 00 00 6C 24 00 00 FC 24 00 00 .$..|$..l$..ü$..

00402020: 00 00 00 00 08 23 00 00 12 23 00 00 28 23 00 00 .....#...#..(#..

00402030: 3C 23 00 00 4A 23 00 00 56 23 00 00 62 23 00 00 <#..J#..V#..b#..

00402040: 6C 23 00 00 78 23 00 00 00 23 00 00 B0 23 00 00 l#..x#...#..°#..

00402050: B8 23 00 00 C2 23 00 00 D0 23 00 00 DE 23 00 00 ,#..A#..D#.._#..

00402060: E8 23 00 00 FA 23 00 00 0A 24 00 00 24 24 00 00 è#..ú#...$..$$..

00402070: 3A 24 00 00 54 24 00 00 F8 22 00 00 E6 22 00 00 :$..T$..o"..æ"..

00402080: D6 22 00 00 C8 22 00 00 BA 22 00 00 A2 22 00 00 Ö"..E"..º"..¢"..

00402090: 9A 22 00 00 8C 23 00 00 90 22 00 00 00 00 00 00 ."...#..."......

004020A0: 00 00 00 00 39 11 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....9.@.........

004020B0: 80 10 40 00 3B 15 40 00 34 13 40 00 00 00 00 00 ..@.;.@.4.@.....

004020C0: 57 68 61 74 20 69 73 20 79 6F 75 72 20 6E 61 6D What is your nam

004020D0: 65 3F 20 00 25 33 31 73 00 00 00 00 59 6F 75 72 e? .%31s....Your

004020E0: 20 73 65 63 72 65 74 20 63 6F 64 65 20 69 73 3A secret code is:

004020F0: 20 00 00 00 58 30 40 00 A8 30 40 00 00 00 00 00 ...X0@."0@.....

00402100: 48 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 H...............

00402110: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00402120: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00402130: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 18 30 40 00 .............0@.

00402140: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00402150: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 ........_ÿÿÿ....

00402160: D4 FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 99 12 40 00 Oÿÿÿ...._ÿÿÿ..@.

00402170: AD 12 40 00 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 -.@....._ÿÿÿ....

00402180: D8 FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 39 14 40 00 Oÿÿÿ...._ÿÿÿ9.@.

00402190: 4C 14 40 00 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 L.@....._ÿÿÿ....

004021A0: CC FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 FE FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 Iÿÿÿ...._ÿÿÿ....

004021B0: 10 16 40 00 14 22 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ..@.."..........

004021C0: AC 22 00 00 24 20 00 00 F0 21 00 00 00 00 00 00 ¬"..$ ..d!......

004021D0: 00 00 00 00 18 25 00 00 00 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 .....%... ......

004021E0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004021F0: E8 24 00 00 D8 24 00 00 C6 24 00 00 AC 24 00 00 è$..O$..Æ$..¬$..

00402200: 96 24 00 00 7C 24 00 00 6C 24 00 00 FC 24 00 00 .$..|$..l$..ü$..

00402210: 00 00 00 00 08 23 00 00 12 23 00 00 28 23 00 00 .....#...#..(#..

00402220: 3C 23 00 00 4A 23 00 00 56 23 00 00 62 23 00 00 <#..J#..V#..b#..

00402230: 6C 23 00 00 78 23 00 00 00 23 00 00 B0 23 00 00 l#..x#...#..°#..

00402240: B8 23 00 00 C2 23 00 00 D0 23 00 00 DE 23 00 00 ,#..A#..D#.._#..

00402250: E8 23 00 00 FA 23 00 00 0A 24 00 00 24 24 00 00 è#..ú#...$..$$..

00402260: 3A 24 00 00 54 24 00 00 F8 22 00 00 E6 22 00 00 :$..T$..o"..æ"..

00402270: D6 22 00 00 C8 22 00 00 BA 22 00 00 A2 22 00 00 Ö"..E"..º"..¢"..

00402280: 9A 22 00 00 8C 23 00 00 90 22 00 00 00 00 00 00 ."...#..."......

00402290: 20 06 70 72 69 6E 74 66 00 00 30 06 73 63 61 6E .printf..0.scan

004022A0: 66 00 49 06 73 74 72 6C 65 6E 00 00 4D 53 56 43 f.I.strlen..MSVC

004022B0: 52 31 31 30 2E 64 6C 6C 00 00 6F 01 5F 58 63 70 R110.dll..o._Xcp

004022C0: 74 46 69 6C 74 65 72 00 05 02 5F 61 6D 73 67 5F tFilter..._amsg_

004022D0: 65 78 69 74 00 00 A4 01 5F 5F 67 65 74 6D 61 69 exit..☼.__getmai

004022E0: 6E 61 72 67 73 00 E0 01 5F 5F 73 65 74 5F 61 70 nargs.à.__set_ap

004022F0: 70 5F 74 79 70 65 00 00 BC 05 65 78 69 74 00 00 p_type..¼.exit..

00402300: 69 02 5F 65 78 69 74 00 1C 02 5F 63 65 78 69 74 i._exit..._cexit

00402310: 00 00 2C 02 5F 63 6F 6E 66 69 67 74 68 72 65 61 ..,._configthrea

00402320: 64 6C 6F 63 61 6C 65 00 E2 01 5F 5F 73 65 74 75 dlocale.â.__setu

00402330: 73 65 72 6D 61 74 68 65 72 72 00 00 EF 02 5F 69 sermatherr..ï._i

00402340: 6E 69 74 74 65 72 6D 5F 65 00 EE 02 5F 69 6E 69 nitterm_e.î._ini

00402350: 74 74 65 72 6D 00 A5 01 5F 5F 69 6E 69 74 65 6E tterm.¥.__initen

00402360: 76 00 84 02 5F 66 6D 6F 64 65 00 00 2B 02 5F 63 v..._fmode..+._c

00402370: 6F 6D 6D 6F 64 65 00 00 3B 01 3F 74 65 72 6D 69 ommode..;.?termi

00402380: 6E 61 74 65 40 40 59 41 58 58 5A 00 98 01 5F 5F nate@@YAXXZ...__

00402390: 63 72 74 53 65 74 55 6E 68 61 6E 64 6C 65 64 45 crtSetUnhandledE

004023A0: 78 63 65 70 74 69 6F 6E 46 69 6C 74 65 72 00 00 xceptionFilter..

004023B0: 6C 03 5F 6C 6F 63 6B 00 D6 04 5F 75 6E 6C 6F 63 l._lock.Ö._unloc

004023C0: 6B 00 1B 02 5F 63 61 6C 6C 6F 63 5F 63 72 74 00 k..._calloc_crt.

004023D0: 9C 01 5F 5F 64 6C 6C 6F 6E 65 78 69 74 00 12 04 ..__dllonexit...

004023E0: 5F 6F 6E 65 78 69 74 00 F6 02 5F 69 6E 76 6F 6B _onexit.ö._invok

004023F0: 65 5F 77 61 74 73 6F 6E 00 00 2F 02 5F 63 6F 6E e_watson../._con

00402400: 74 72 6F 6C 66 70 5F 73 00 00 60 02 5F 65 78 63 trolfp_s..`._exc

00402410: 65 70 74 5F 68 61 6E 64 6C 65 72 34 5F 63 6F 6D ept_handler4_com

00402420: 6D 6F 6E 00 3B 02 5F 63 72 74 5F 64 65 62 75 67 mon.;._crt_debug

00402430: 67 65 72 5F 68 6F 6F 6B 00 00 9A 01 5F 5F 63 72 ger_hook....__cr

00402440: 74 55 6E 68 61 6E 64 6C 65 64 45 78 63 65 70 74 tUnhandledExcept

00402450: 69 6F 6E 00 99 01 5F 5F 63 72 74 54 65 72 6D 69 ion...__crtTermi

00402460: 6E 61 74 65 50 72 6F 63 65 73 73 00 3C 01 45 6E nateProcess.<.En

00402470: 63 6F 64 65 50 6F 69 6E 74 65 72 00 3C 04 51 75 codePointer.<.Qu

00402480: 65 72 79 50 65 72 66 6F 72 6D 61 6E 63 65 43 6F eryPerformanceCo

00402490: 75 6E 74 65 72 00 28 02 47 65 74 43 75 72 72 65 unter.(.GetCurre

004024A0: 6E 74 54 68 72 65 61 64 49 64 00 00 F4 02 47 65 ntThreadId..ô.Ge

004024B0: 74 53 79 73 74 65 6D 54 69 6D 65 41 73 46 69 6C tSystemTimeAsFil

004024C0: 65 54 69 6D 65 00 11 03 47 65 74 54 69 63 6B 43 eTime...GetTickC

004024D0: 6F 75 6E 74 36 34 00 00 17 01 44 65 63 6F 64 65 ount64....Decode

004024E0: 50 6F 69 6E 74 65 72 00 83 03 49 73 44 65 62 75 Pointer...IsDebu

004024F0: 67 67 65 72 50 72 65 73 65 6E 74 00 88 03 49 73 ggerPresent...Is

00402500: 50 72 6F 63 65 73 73 6F 72 46 65 61 74 75 72 65 ProcessorFeature

00402510: 50 72 65 73 65 6E 74 00 4B 45 52 4E 45 4C 33 32 Present.KERNEL32

00402520: 2E 64 6C 6C 00 00 .dll..

The expected string constants appear at 004020C0 and consume 49 bytes. It seems that most or all of the data before and after those strings is part of the imports list. The PE header contains a bunch of offsets to the import data, but the import data itself can be located anywhere in the executable file. Apparently the linker has chosen to place it here in the .rdata section.

As best as I can tell from examining code disassemblies, most of the bytes before the string constants (00402000 to 0040209C) are a table of function pointers that will be filled in by the loader, belying the “read only” nature of this section. I guess “read only” only applies to the program itself once it starts running, and not actions performed by the loader. For example, after the loader has loaded the C runtime library DLL and determined the address of the printf function, it will place that address into one of these table entries. The main code can then use that table entry to call printf indirectly when needed.

After the strings but before the imported function names, there are 416 bytes from 004020F0 to 0040228F that appear unrelated to the imports list or any easily-identifiable code. From examining the code disassembly, it appears these are used by some mystery library code that’s inserted into the executable, but I’ve been unable to determine what it’s for.

The bytes from 00402290 onward are the actual names of the imported DLLs and the functions needed from each one. It’s a little curious that these are stored as plain text function names, instead of by index in the DLL or by a hash of the function name. I guess a few bytes wasted here isn’t very important.

.data

Next I’ll look at the .data section, for initialized data that’s both readable and writable. The example program doesn’t have any global variables or other structures that would obviously go in the .data section, so it’s not clear what’s consuming 908 bytes here. Let’s look:

SECTION HEADER #3

.data name

38C virtual size

3000 virtual address (00403000 to 0040338B)

200 size of raw data

1400 file pointer to raw data (00001400 to 000015FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

C0000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Write

RAW DATA #3

00403000: 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403010: FE FF FF FF FF FF FF FF 4E E6 40 BB B1 19 BF 44 _ÿÿÿÿÿÿÿNæ@»±.¿D

00403020: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403030: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403040: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403050: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403060: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403070: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403080: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403090: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030A0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030B0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030C0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030D0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030E0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004030F0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403100: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403110: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403120: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403130: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403140: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403150: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403160: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403170: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403180: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00403190: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031A0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031B0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031C0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031D0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031E0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

004031F0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

Hmm, there’s not a lot of initialization going on in this initialized data section, unless it’s a whole lot of things being initialized to zero. Nothing recognizable jumps out from the data. From examining the code disassembly for references to this area of memory, it looks like this space is used by about 40 global variables, most of which are 2 or 4 bytes, but with a few larger ones. It seems a little wasteful to store so many zeroes in the executable file when those variables could have been stored in an uninitialized section instead (.bss). But due to the 512 byte alignment requirement for the section, any zero data after the real initialized data will be free, because those zeroes have to be there anyway for alignment padding.

So what is all this stuff? The disassembly shows that some of it is related to the state of the terminal window, and some of it may be used in conjunction with handling of the command line args. Some of it looks like a place to save the processor state – maybe as part of a debugger integration or core dump capability (!). Most of it is referenced by blocks of code whose purpose is a complete mystery to me. Why is all this junk here, even when I’ve turned off every compiler and linker option I could find that suggested it would add extra “features” to my program? I’m beginning to feel like I’ve lost control of my own creation. Why can’t I get rid of all this extra junk, and only have the code and data that I put there myself?

.text