Uzebox

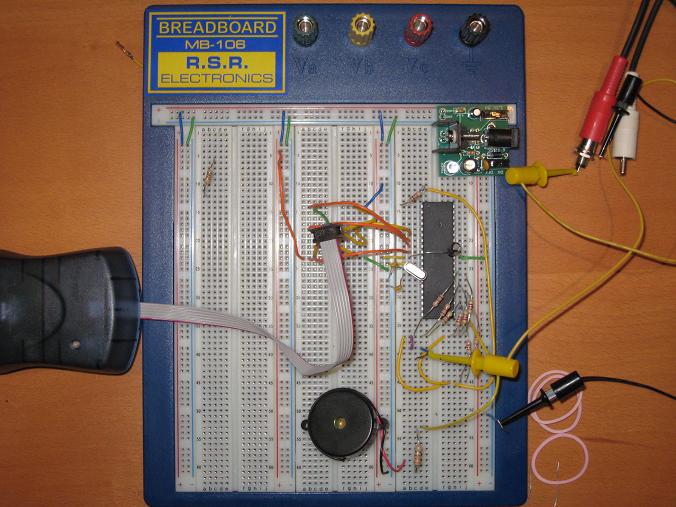

I’ve decided to build a minimal Uzebox. The Uzebox is a software-generated video game system based on an open source hardware design. It uses an ATMega644 microcontroller with 4K RAM to synthesize a composite video signal and sound on the fly, line by line. The official Uzebox design uses an Analog Devices AD725 RGB-to-composite chip, along with an SD card interface, and MIDI and joystick ports. I really wanted something super-minimal, though, so I dropped everything from the system except the ‘644 itself, the power supply, a piezo speaker, and some resistors and capacitors. I think it’s about as bare bones as you can get. Here’s what I came up with:

To replace the AD725 color chip, I constructed a grayscale binary weighted DAC from nine resistors. The eight color bits and the sync signal from the ‘644 are combined. I did some math to solve for the correct resistor values to produce 1 volt when all the colors bits are 1’s, and 0.3 volts when all the color bits are 0’s, assuming the sync signal is 1 in both cases. I must be getting dumber in my old age, because it took me a long time to churn through the math, and I eventually had to ask my wife to help. This was the result:

This seems right mathematically, but when I tried it connected to the TV, the resulting voltage was too low. When I removed the 75 Ohm resistor, everything looked nearly perfect. I don’t really understand that… should the video cable and TV itself be treated as a 75 Ohm resistor to ground in this calculation? Something about impedance matching that I don’t really grasp.

With the 75 Ohm resistor removed, I burned a Pac-Man game into the ‘644, connected the breadboard to the living room TV, and was rewarded with this:

The image quality is middling, but it’s not too bad for a quick breadboard job. The grayscale is definitely working, although it’s hard to see in this picture. The ghosts show the grayscale levels best.

Unfortunately I couldn’t get the Uzebox to work with the composite video input on my Dell monitor. It didn’t show anything at all, behaving the same as if nothing was even plugged in. I’m assuming this is because my video signal is too noisy, or out of spec somehow, and the monitor is more picky about signal quality than the TV. I looked at the video signal on the oscilloscope, though, and it looks pretty decent to me. Not too much noise, baseline is right at 0.3 volts, HSYNC pulses look fine. The brightest parts of the image do overshoot to about 1.25 volts, but I wouldn’t guess that would be a huge problem. I need to find a solution, though, because hauling the whole thing into the living room for every test isn’t too practical.

Although my interest here is primarily in the hardware, it’s damn impressive that this single ATMega644 with just 4K RAM is able to generate all the video and audio for a very faithful Pac-Man recreation. Remember, there’s no frame buffer. The video signal is generated on the fly, line by line, pixel by pixel, in the midst of all the other necessary game-related computation.

Read 12 comments and join the conversationBMOW Shirts

BMOW shirts arrived today. Not a giveaway– just enough for family and crew at the Maker Faire.

Software-Generated Video

I’ve become interested in software generated video, after reading the book The Black Art of Video Game Console Design by André LaMothe. It’s a unique book, covering everything from atomic theory all the way up to building your own embedded computer system. Unfortunately it’s plagued by a million errors, but I was still fascinated by the idea of direct synthesis of video in software, which is part of the design of the game system discussed in the book.

Most computer systems (including BMOW) have dedicated video display hardware. The CPU writes data to video memory, and at the same time, the display hardware reads data from video memory and synthesizes the actual analog voltages that constitute the video signal for the monitor or TV. In BMOW the display hardware consists of fourteen separate chips, including the video memory itself, character generator, counters for the current row and column, shifter, oscillator, various registers and buffers, and a RAMDAC. It took a long time to design, but it’s pretty powerful.

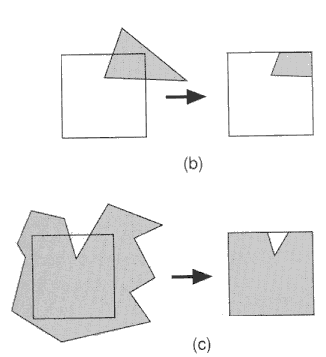

In contrast, software-generated video creates the final video signal voltages directly from the CPU or microcontroller pins, with no intervening hardware at all except a handful of resistors to form a simple R2R DAC. You’ve got a MCU, some resistors, and that’s all. It generates the video signal in real time, on the fly, and there’s no need for any video memory or frame buffer. Fascinating stuff. The downside is that you need a fast MCU, and your code must be deterministic and per-clock-cycle exactly identical from scanline to scanline. Almost all the processing power is consumed by generating the video, so there’s little left for other logic, and logic code must be interleaved with the video code. I was vaguely aware of this technique before, but never really looked at it deeply because of all these problems with it. At least, that was the case until I saw some of the things the XGameStation from LaMothe’s book can do.

Check out the XGameStation Micro Edition web page. That’s some fairly impressive stuff from a little microcontroller and software-generated video. I decided I wanted to build one of these myself, as a short but interesting detour from work on 3D Graphics Thingy. Most of the XGameStation systems are prebuilt systems, which don’t interest me much, but there’s also the XGameStation Pico Edition that you can put together yourself. Perfect! Except it’s pretty expensive for what you get. I just can’t stomach paying $60 for a kit that contains a $3 microcontroller and a bunch of passive components that I mostly already own anyway. To make matters worse, a $50 SX-Key is also required to program the SX28 microcontroller, bringing the total cost to $110 for a simple little breadboard project.

I did some research, and found that I can get all the parts I need from the $60 Pico Edition kit for under $10 total, except one: the 78.75 MHz clock oscillator. In order to generate color video, you need a high-speed clock that’s an integer multiple of the base NTSC frequency of 3.579545 MHz. Sadly, these just don’t seem to exist anywhere that I’ve found. The only solution appears to be to buy a programmable oscillator, which is what the kit contains, I think. But programmable oscillators with the speed and precision needed are pretty expensive, and only sold in large quantities. Without that oscillator, it’s possible to generate black and white NTSC video only. Of course this still doesn’t change the need for the $50 SX-Key, for which I’ve found no alternative and no used ones for sale. Sigh.

As an alternative, I also looked into making a simple software-generated video system from a PIC24, which is at the heart of another XGameStation design. That’s a little more questionable, since there’s no specific “Pico” design using the PIC24 whose software I could use, but there is a wider selection of tools and software for the PIC series than the SX28. But the same oscillator requirements exist, and while the PicKit2 programmer is a little cheaper than the SX-Key, it’s still not cheap.

At the moment then I’m stuck, and not sure if I should pursue this idea any further. The microcontroller and other parts can be had for just a couple of bucks, so it’s a bit frustrating that the oscillator and programmer requirements are turning this into a $100+ project.

Read 21 comments and join the conversationMore Swag

I’ve been going a little overboard with all the BMOW stuff for the Maker Faire. I’ve spent about $300 on assorted stuff, which is a little crazy considering that this isn’t a profit-making enterprise, and there’s really no good reason to have stickers and posters and books and things, but I can’t stop myself. Help, I think I have a problem!

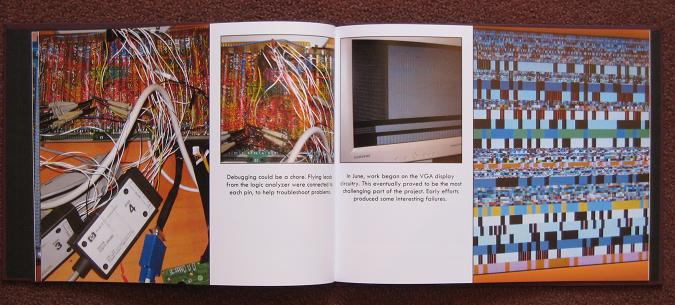

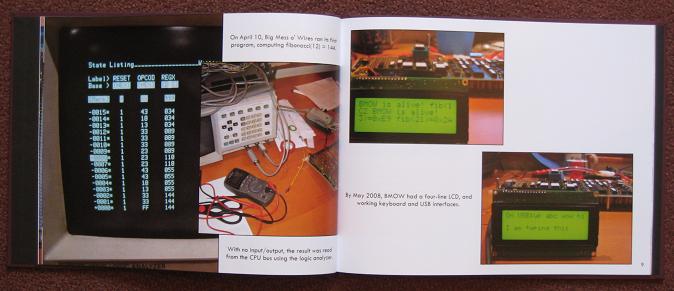

I used Shutterfly to print four large photos of the wiring side of the BMOW main board, which I’ll have around the booth at the Maker Faire. While I was browsing the the Shutterfly site, I also noticed a special they were running: a twenty page 8 x 11 inch hardcover photo book for $23. I couldn’t resist, so I spent a few hours designing a “Making of BMOW” book for people to browse at the booth. It’s a condensed version of the past year and a half of this blog. The book arrived yesterday, and it’s awesome! The front cover has a hole cut in it, framing the photo on the title page, which is a nice touch.

Here are a couple of sample pages from inside the book. It all looks really professional.

I should have stopped there, but I didn’t. Another idea I’ve been mulling for a while is creating a clear cover for the BMOW case. I’m a little worried it might get damaged or spilled upon if I leave the case cover off during the Maker Faire, but with the existing cover in place, it becomes just a boring beige box. I wasn’t really sure how to go about making a custom clear cover though, and never took the idea any further.

Last week it occured to me that a custom clear cover doesn’t really need to be a complete replacement for the metal cover, with full sides, back, guide rails, and so forth. All I really need is a 2D cover that can be mounted to the system board using standoffs, and will protect the board from most hazards from above. That would still leave some small gaps at the sides and edges, but they’d be small enough to not be worrisome. So I took some measurements, spent an hour designing a cover using Corel Draw, and mailed the file off to Pololu, a company that does custom laser cutting of various materials.

The cover arrived yesterday, and it’s pretty much the coolest thing ever. It’s 1/8″ clear acrylic, with laser cut mounting holes, and a grille for the speaker. The BMOW logo is also etched into the cover, using the laser at a low-power setting so it didn’t burn all the way through.

I’m just blown away that I can spend an hour in a vector drawing program, send the file off into the ether, and three days later get an exact physical part on my doorstep for $29. I’ll definitely be looking for more excuses to custom fabricate parts in the future.

I haven’t yet confirmed that the cover fits, since I need to get the correct size standoffs first. It looks perfect to an eyeball test, though. My vector layout file was based on hand-measurements made with a ruler, so it’s entirely possible that the mounting hole positions are slightly off. I made the hole diameters bigger than needed to allow for some error, and if worse comes to worse, I’ll try drilling out the holes to correct any major mismeasurements.

Read 11 comments and join the conversationFPGA Research

Over the past few days I’ve done a huge amount of reading about both 3D graphics hardware and FPGAs, and I’m starting to get a better picture in my mind of how this 3D Graphics Thingy might be built. My surprising conclusion is that 3DGT may not require any custom hardware at all, but could be entirely implemented using an off-the-shelf FPGA development board. This is either good or bad, depending on your point of view.

Looking back at my earlier “construction notes” posting, I described a vision of 3DGT as a single-board computer with a CPU, FPGA, RAM, ROM, keyboard, USB, and VGA output. That more or less exactly describes an FPGA development board. All the work would then go into creating the HDL for the graphics pipeline, which would be programmed into the FPGA, turning 3DGT into a mostly firmware project. There would still be a few missing hardware pieces when using an FPGA development board, however:

- CPU – I still need a CPU to drive the graphics pipeline, and determine what to draw. Some high-end FPGAs actually have a CPU built-in, but those are out of my price range. My first approach will be to embed a “soft CPU” into the FPGA along with everything else. Xilinx provides a PicoBlaze 8-bit soft CPU that only consumes about 5% of the space in a Spartan 3 FPGA. There’s also the OpenRISC soft CPU from OpenCores.org, if something more powerful is needed. And if a soft CPU doesn’t work out, I can add a real CPU on a daughter card, attached to the development board’s expansion connector.

- VGA – There are lots of development boards with integrated VGA hardware. However, the cheaper boards are all limited to a few bits per color channel. The best I’ve seen is 4:4:4 12-bit color. That will be great for initial testing, but ultimately I’ll need to add a separate 8:8:8 video DAC on a daughter card.

- Joystick, etc – Connecting a gamepad will require a bit of custom hardware, also on a daughter card. Any sound hardware would need to be external to the daughter board too. For initial testing, I can use the built-in keyboard connection.

I like where this is going, although it’s a lot less hardware-oriented than I’d initially expected. Essentially, I can purchase an FPGA development board and get started immediately, using a soft CPU, low bit-depth VGA, and keyboard input. Once the guts of the graphics pipeline are mostly working, I can expand by adding a daughter card with a CPU, video DAC, gamepad connector, etc. For the final version I might create a custom single-board PCB for exactly the hardware I need, and ditch the development board, or just keep the development board + daughter board as the final hardware.

The development boards I’m considering are Xilinx’s Spartan-3E Starter Kit and Spartan-3A Starter Kit. These seem to be the best fit as far as including the parts I need, without a lot of other parts I don’t need, or costing a million dollars. There’s also a wealth of information and tutorials online about how to use these boards, from Xilinx and third parties.

Both boards include the FPGA, 32MB RAM, 16 or 32MB Flash ROM, VGA, USB, PS/2 keyboard input, two serial ports, ethernet, and a two-line LCD. I don’t need the serial ports or Ethernet, of course, but there they are. Both kits come with 50MHz clock oscillators built-in, but I couldn’t find any data on their maximum possible speeds, or the speed grades of the specific FPGAs.

- 3E – The $149 3E is the older board, with a XC3S500E sporting 10476 logic cells, 360K bits of block RAM, and 20 dedicated multipliers. The major drawback is that the VGA output is 1:1:1, allowing for just 8 colors. That would let me work on triangle rasterization, but not color interpolation or texturing. If I ever want to ditch the development board and make a custom PCB, though, the 3E kit is the way to go. The exact same FPGA is available from Sparkfun in a breakout board, as well as from other vendors, or it can also be purchased as a bare IC with leads that I can solder myself.

- 3A – The $189 3A is the newer board, hosting a XC3S700A. The 3A has 13248 logic cells, 360K bits of block RAM, and 20 dedicated multipliers. The larger number of logic cells is nice, but the big advantage of this kit is the 4:4:4 VGA interface, enabling 4096 colors. The drawback is that if I later want to drop the development board and make a custom PCB, it’ll be difficult to do without switching away from the 3A. It’s only available in a leadless BGA package that I can’t hand-solder, and I haven’t found any 3A breakout boards or adapters advertised online.

Along with all this research into the development hardware, I also did some reading about other similar 3D graphics FPGA projects, hoping I might learn from them. Maybe I didn’t dig hard enough, but I didn’t find much, and what I did find were all unfinished projects:

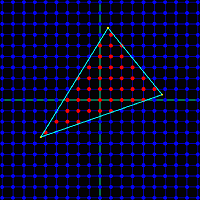

- Manticore – A project started by two students at the University of Alberta in 2002, but never finished. They implemented a basic rasterizer that will be very interesting to examine, as well as a memory controller to arbitrate memory requests and talk to DRAM. They never worked out all the bugs in the rasterizer though, and the design lacks a z-buffer and texture mapping.

- Niklas Knutsson Thesis Project – A 2005 Master’s thesis from Linköping University, Sweden. This is a great description of the task of implementing a 3D graphics pipeline in an FPGA, but the implementation was never finished. He got as far as drawing some basic test patterns, but most of the design time was spent on the CPU and memory controller, so the 3D pipeline wasn’t fully fleshed out. The HDL source and schematics don’t seem to be available online, unfortunately.

- Open Graphics Project – This is an ongoing project to build a fully PC-compatible graphics card, using a pair of FPGAs on a PCI card. Coincidentally, it was featured on the front page of Slashdot just yesterday. The majority of the development so far appears to have centered on the PCI interface, and support for legacy VGA modes. The documentation on the 3D pipeline is fairly skeletal, and it appears that little of it has actually been implemented so far.

I’m surprised there aren’t more projects out there like this, and apparently none that were ever successful. I’m guessing that such projects do exist, and I’ll just have to dig a little deeper to find them.

Read 7 comments and join the conversation3D Breakdown

OK, enough discussion of FPGA gate counts for the time being. It’s time to talk about how this 3D Graphics Thingy might work, at a functional level. My current thinking is to divide the system into four major pieces:

CPU – Determines what objects are visible to the camera

Vertex Processor – Transforms and lights object vertices

Pixel Processor – Fills the interiors of polygons

Video Buffer – Stores and displays an image on the screen

The only pieces that are strictly necessary for 3D graphics are the CPU and video buffer, since the CPU could do all the necessary computations in software, but the result would be incredibly slow. Implementing vertex and pixel processing in dedicated hardware will dramatically increase the number of polygons per second that can be drawn. This entire project boils down to just a performance optimization then, albeit a complex one. Adding vertex and pixel processors will improve performance through parallelization across multiple hardware units, and pipelining within a unit.

Video Buffer

The core of the video buffer is just some dedicated memory for storing a screen image, and hardware to scan that memory and generate a VGA-compatible video signal. I’ve already implemented a video buffer previously for BMOW, so this is familiar territory. However, the 3DGT video buffer will differ from BMOW’s in several respects.

Bit depth – Images will be stored in video memory in a direct color format, with somewhere between 16 and 32 bits per pixel. Each pixel’s data will be directly interpreted as 5:5:5 or 8:8:8 RGB data, and sent to a high-speed RAMDAC to create the three analog color voltages for the VGA signal. This will require larger, faster video memory than BMOW, which has 8 bits per pixel used as an index into a secondary color palette, which determines the final RGB color.

Contents – In addition to the framebuffer for the currently displayed image, the video buffer memory will also contain other types of video-related data. Depending on the final design, this may include a backbuffer to support double-buffering, a depth buffer to support hidden surface removal, and texture image data.

Access – Getting data in and out of the video buffer quickly will be essential for good performance. Several 8-bit RAMs will probably be used in parallel, to permit reading and writing of 32 bits or more at a time. A solution for providing simultaneous access to both the CPU and display circuitry is also essential. This is noticeably lacking with BMOW, causing visible “noise” on the screen during CPU access to the video buffer. I have a few ideas on how to accomplish this, with various pros and cons, which I’ll describe in a later posting about the video buffer details.

The video buffer is a critical component of the 3DGT system, and also the one I’ll need to implement first. However, it’s also the one I find least interesting. Other than the question of avoiding CPU/display memory contention, the rest of the video buffer functionality is relatively straightforward and boring. I won’t feel guilty about reusing purpose-made parts or VHDL libraries for this piece, so I can move on more quickly to the more interesting bits.

Pixel Processor

This is where most of the real interesting action will occur. It’s the pixel processor that will primarily determine what kind of graphics features 3DGT supports, and what sort of performance it has. Most of my design work will be here, and the FPGA will probably be filled by units of the Pixel Processor more than anything else.

So what does a pixel processor do? It’s supplied with the X,Y,Z coordinates of three vertices for a triangle. It may also be supplied with color, texture, and other data about each vertex.

First, the pixel processor must determine which screen pixels are inside the triangle. This involves some math that’s somewhat complicated to describe, and much more complicated to imagine implementing efficiently in hardware. There are also some interesting boundary cases, like to how to handle pixels that are mathematically exactly on a triangle edge. Count them in, and they’ll also be drawn by an adjacent triangle that shares that edge, causing a double-draw. Count them out, and the pixel won’t be drawn by the adjacent triangle either, creating a gap.

For every pixel that’s inside the triangle, the pixel processor must interpolate the values from the vertices to determine intermediate values at that pixel. For example, if the top-left vertex is supposed to be white, and the top-right vertex is supposed to be black, then a pixel about 75% of the way along the top edge should be dark gray. Interpolation is further complicated by the fact that 2D screen space interpolation (such as my dark-gray example) isn’t actually mathematically correct. If that top-right vertex had a much greater Z value than the top-left one, implying the 2D projection of a 3D edge that disappears away and to the right, then 75% gray would look subtly wrong. To be accurate, perspective-correct interpolation must be formed, but this is more challenging and expensive to implement in hardware. Early 3D hardware such as the Playstation did screen-space interpolation, but all modern 3D hardware does perspective correct interpolation.

Once the interpolated values are determined, each interior pixel must be drawn into the video buffer memory. This involves several considerations:

Z-depth – Has something else already be drawn which covers this pixel and is closer to the camera? If so, it should obscure this triangle, and further processing of this pixel for this triangle can be aborted.

Texture Lookup – Most triangles will be textured, instead of just being solid colors. This means a portion of a 2-dimensional texture image stored elsewhere in the video buffer must be “glued” onto the triangle. The correct pixel from the texture must be fetched, and combined with the interpolated color value for this pixel.

Texture Blending – When applying textures to a triangle, the resulting image may be larger or smaller than the original texture, depending on the size of the triangle to which it’s applied. This effectively results in scaling the texture image. The scaling can be done using point sampling, which requires looking up a single texture pixel for each screen pixel, or with various types of filtering, which require looking up many texture pixels and combing the result.

Alpha Blending – The vertex color, texture color, or both may include an alpha component along with the RGB components. If supported by the hardware, alpha blending allows for the specification of translucent colors, and the alpha value determines the degree of opacity of the color. Implementing alpha blending in hardware requires reading the color value that was already in the video buffer at this pixel, computing a weighted average with the new color value, and writing the result back. As a result of this extra step, alpha-blended polygons are more expensive to draw than opaque ones. The left frame below shows a red sphere composed of opaque polygons, while the right frame shows a translucent sphere rendered with polygons using alpha blending.

Fogging – In the real world, objects in the far distance appear hazy and with desaturated colors due to atmospheric effects. This is an important visual cue to indicate that an object is far away, and synthetic 3D scenes containing distant objects in eye-popping bright colors look unnatural. Hardware can provide this effect, called fog, by computing a weighted average of the polygon color with a global fog color (typically grayish-blue), according to the Z-depth of each pixel. Fog can be computed as a linear function of Z, or using more complex functions for better-looking results.

Custom Pixel Shaders – The ultimate in flexibility is to provide a custom pixel “shader”, which is just a small program that’s run by the pixel processor to compute the result for each pixel. All modern graphics hardware uses pixel shaders, which permit any crazy set of rules you can imagine to determine the final color. Older fixed-function graphics hardware allowed various built-in features like alpha blending and fogging to be turned on and off, but could not perform any custom pixel operations not explicitly built-in.

3DGT will likely be a fixed-function graphics system, in order to keep the project complexity down. I hope that it will support all the other features of z-sorting, alpha blending, texture mapping, and fogging, but it will depend on how complex those tasks prove to be. If they all prove too daunting, a credible but basic 3D system could still be constructed without any of them, using the CPU to sort polygons by depth, and rendering solid colored triangles. If the polygon count is high enough, and per-vertex lighting is performed, the result could even look quite good. Here’s an example:

I’ve described the pixel processor as if it were a sequential state machine, evaluating one pixel of one triangle at a time. This will almost certainly not be the case, as substantial speedups can be gained here with the right hardware design.

The computation of each pixel can be pipelined, so for example the alpha blending of one pixel might proceed concurrently with the z-test of the next pixel. The texture processor will likely have a large number of pipeline stages, since subdivision of a repeated task into n stages of equal duration yields an improvement of n in overall throughput.

Pixel computation can also be parallelized, by creating many pixel processing subunits, and assigning each to a different region of the screen. Because the color of each pixel is unaffected by its neighbors, the subunits could operate completely independently. However, additional hardware would be required to farm triangles out to the correct subunits, and to avoid contention between the subunits for the same RAM chips.

Vertex Processor

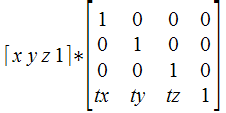

Like the pixel processor, the vertex processor also receives data about the vertices of triangles. In the case of the vertex processor, this data is supplied by the CPU. Vertex positions for an object are specified in object space, which is the fixed 3D coordinate system in which that object was modeled. The vertex processor is also supplied with information about the object’s position and orientation in the world, as well as the camera’s position and orientation, and parameters like the camera zoom factor. From this, a projection matrix can be constructed to transform vertices from world space to camera space, and from camera space to screen space.

Thus the primary job of the vertex processor is to do lots of multiplications of vectors with matrices. And since that task can be broken down into multiplication of vectors by columns of the matrix, all the hardware really needs is to multiply vectors by vectors, computing the dot product. Multiply and accumulate is the name of this game, since the dot product of two vectors [ x0, y0, z0 ] and [ x1, y1, z1 ] is just x0*x1 + y0*y1 + z0*z1.

By the way, the singular form of vertices is vertex. The singular of matrices is matrix. Every time I hear someone construct a new singular word “verticee” or “matricee” by incorrect derivation from the plural, I have to resist the urge to laugh. Unfortunately, this seems to be a common mistake, at least when speaking, if not when writing.

In addition to projecting vertex positions into screen space, the vector processor is also responsible for lighting each vertex. In this context, lighting means determining what color should be assigned to the vertex, passed to the pixel processor, and then interpolated across the face of the polygon. There are a tremendous number of different ways to compute lighting, but the simplest is to compute max(0, n dot l), where n is a unit normal vector pointing away from the polygon’s face in the “outside” direction, and l is a unit normal vector from the vertex in the direction of the light source. Where the light is shining directly down on the surface, n and l are coincident, so n dot l = 1 and the vertex is maximally lit. When the light is shining tangentially to the surface, and n and l are perpendicular, so n dot l = 0 and the vertex is not lit. When the light is shining from behind the surface, n and l point in opposing directions, so n dot l is less than 0, and max(0, n dot l) evaluates to 0, and once again the vertex is not lit.

The vertex processor can also implement an optimization known as back face culling. For a solid 3D object, every triangle on its surface has a front and a back face. A moment’s thought shows that the back faces can never be seen, because they will always be obscured by the front face of another triangle on the other side of the object. The vertex processor can detect back faces easily, since the normal vector for a back face always points away from the camera position. Back faces can be rejected by the vertex processor, and don’t need to be sent to the pixel processor at all. However, this optimization only works for solid 3D objects. A 2D object in a 3D space, like a leaf, must have both faces visible.

Another important job of the vertex processor is clipping. Imagine that after projection into screen space, two of the three vertices lie within the boundaries of the screen, and one lies outside. The pixel processor is typically not equipped to deal with this- it assumes all vertex positions are within the boundaries of the screen, and may “wrap around” and begin filling pixels at the opposite side of the screen while trying to fill a triangle that extends beyond the screen’s edge. To rectify this, the vertex processor must clip the triangle, inserting new vertices and creating two or more new triangles that lie completely within the screen’s boundaries. Colors, normals, and other properties must then be determined for these new vertices by interpolating the values for the original vertices. I fear this is going to be very difficult for me to implement in hardware, but I don’t see any way around it.

Like the pixel processor, the vertex processor can also use custom vertex shaders, or be a fixed-function design. Vertex shaders could be used to generate more advanced effects, like procedurally deforming the vertices in an object, or creating triangles from 3D surfaces such as Bezier patches and NURBS.

CPU

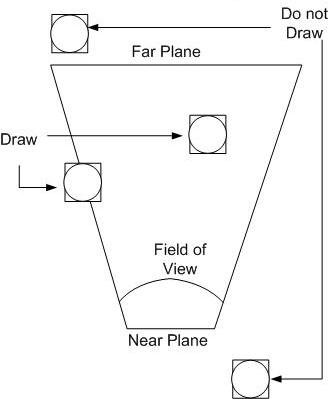

The job of the CPU is to determine the set of objects that must be drawn, and their positions and orientations. As objects move and rotate through the simulated 3D world, the CPU maintains their state. For every frame of video, the CPU considers the state of each object, and the camera’s position and orientation, and determines which objects are potentially visible. This process is known as culling. For example, if an object is behind the camera or off to the side, it can’t possibly be visible, and it’s triangles don’t need to be passed to the vertex processor. Objects that are beyond a maximum distance called the far plane are also culled, so that the camera’s visibility doesn’t extend to infinity.

Putting It All Together

There’s a lot to digest here, and even writing a software simulation of the whole pipeline using C++ would be a substantial task. Implementing it in hardware will definitely require me to learn many techniques I don’t yet know, and at the moment, many of these functions don’t lend themselves to any hardware implementation I can imagine. As I reread what I’ve written, I’m wondering if I haven’t bitten off a larger project than I originally realized. This functional breakdown doesn’t even touch upon questions like the floating point representation used for all these numbers, and how to implement various mathematical operations in hardware. Yet the very existence of 3D graphics hardware going back several decades proves that it can be done. No doubt it’s going to be a challenge, but I’m excited to take it on.

Read 4 comments and join the conversation